To celebrate Juneteenth 2022 in Fairfield, the Carnegie Museum will honor the lives and legacies of Jefferson County’s abolitionists at the Evergreen Cemetery on Monday, June 20. “All these stories are like thumbnail sketches of much larger stories,” says Carnegie director Mark Shafer, who did extensive research for the museum’s brand-new Underground Railroad exhibit, to be unveiled as part of Monday’s Juneteenth festivities. “These graves are like little peepholes into history.”

Many people took their Civil War-era experiences to the grave, Shafer says. But he has heard firsthand memories of people who remembered seeing the eyes of freedom seekers in the dark, or having a parent bring food to the barn. Shafer’s aunts used to play in a well with a large alcove they could both fit in, and now he wonders if it was a hiding place along the road.

The Carnegie’s exhibit paints a portrait of Fairfield in the 1850s and ’60s with a striking resemblance to today’s houses, roads, and farms. Less than two blocks from the cemetery, a slaughterhouse hid freedom seekers by day so they could be driven to the Quaker and Congregationalist community of Pleasant Plain at night. Christian Brykit drove the buggies as a child. He was only 12 years old when he encountered slave catchers. He dropped his rifle and it discharged, spooking the horse. The man who was to ride with him ran into the woods and no one ever found out what happened to him.

“Jefferson County had a lot of pro-slavery and ‘leave them alone it’s not our business’ attitudes,” Shafer notes. “There were wide-ranging views. In the 1840s and ’50s abolitionists were seen as cranky do-gooders who weren’t minding their own business.”

The brother of a Fairfield woman participated in the raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, with abolitionist Dan Brown in Virginia. It’s possible he joined Brown on the Freedom Trail through Iowa in 1859. “The whole story is so complex and undulating and tangled,” Shafer remarks. The brother of another Fairfield resident was imprisoned for “negro stealing” in Ohio while trying to help a freedom seeker to safety, and died of cholera in prison. He became the subject of John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem “The Cross,” and is mentioned in A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote to authenticate her depiction of slavery in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The book’s subtitle is “Presenting the Original Facts and Documents upon Which the Story Is Founded, Together with Corroborative Statements Verifying the Truth of the Work.”

Many farm families quietly helped fugitives on their way to Canada. The Hinshaws, who won first place for their colt at the first Iowa State Fair on what is now 4th and Grimes, hid freedom seekers in their barn during the 1850s and 1860s. The Hayes Farm, Stubbs property, and Hadley properties were all part of the Underground Railroad.

Charles Cook, the first Massachusetts state legislator elected on an abolitionist platform, built his home on the farm near Jasmine Ave. and 155th in Fairfield. “That house stood on the highest hill in the neighborhood,” Shafer said. “We used to go sledding on that hill. In spring plowing season we used to find china and little marbles. We always wondered why someone would build on the north on a hill in all that wind. Well, now we’re speculating it’s so someone could see lights in the window.”

Cook was not the only abolitionist to travel. “We tend to think of people from that time period as staying put,” Shafer says, “but people moved around about as much as today, often by steamboat.” Levi Coffin, sometimes called president of the underground railroad, lived in Ohio and Indiana and was “run out of town more than once and probably jailed” before settling in Fairfield. He helped at least 3,000 people escape slavery. Coffin owned a general store that only sold goods made by free labor.

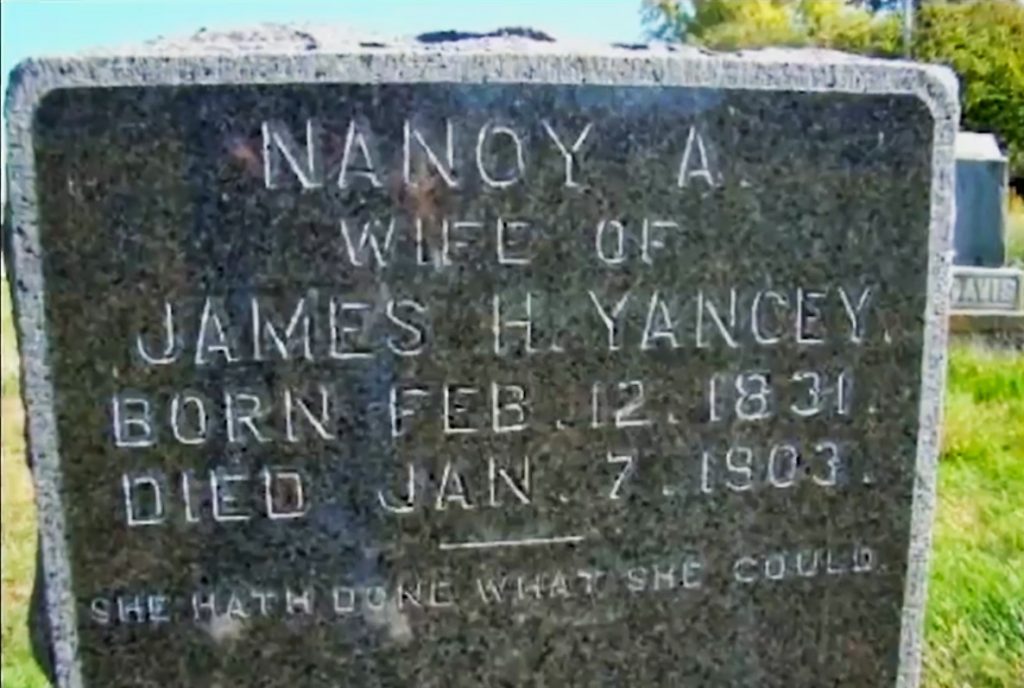

James and Nancy Yancey were the first Black couple to settle permanently in Fairfield. They came from Oberlin, Ohio, with the express purpose of operating an Underground Railroad station. “To give you an idea what kinds of things were happening,” Shafer said, “slave catchers had captured a freedom seeker in a hotel in Oberlin. Abolitionists descended on the hotel, rescued the Black man, took him in a buggy, hid him in the home of a clergyman for a few days, and got him up to Canada. Unscrupulous slave catchers could kidnap people from Iowa and bring them across the border to Missouri,” Shafer went on. “[The Yanceys] were risking life and limb.”

According to her obituary in the Fairfield Ledger, Nancy had been born into slavery in Wheeling, West Virginia, in 1831. She was taken to Ohio where she was “given her freedom,” and attended Oberlin college. Nancy and James married in 1849, and settled in Fairfield in 1857, where they raised seven children. Shafer noted she was “probably better educated than any woman in Iowa at the time, certainly as educated.” The Fairfield Ledger notes she “spent considerable time as a teacher, a work for which she was especially fitted.”

James was a barber who made salves, lotions, and medicinal skin care products. Shafer explained that during that period, barbers commonly did simple surgery like tooth extraction and practiced basic medicine.

At an emancipation celebration in Des Moines on August 1, 1866, James Yancey said, “Is this not a theme to warm the hearts of every person or member of this Nation, both white and black, or no matter of what color, who loves his country and the right? Is not the freedom of a people and the redemption of a nation a theme suited to excite the gratitude of a nation to the extent of its capacity?”

The Yanceys bought a nice house in a middle upper class white neighborhood near Briggs Avenue in Fairfield, although it has since burned down. The family was likely part of the African Methodist Episcopal Church that still stands, hiding in plain sight as a regular-looking home with square windows.

“Their home in this city was ever open to the people of their race, and in the days of slavery many a fugitive from bondage was taken in and cared for by these good people and given a new opportunity to accomplish his freedom,” Nancy’s obituary read.

While Fairfield’s Underground Railroad stations sheltered freedom seekers and helped with transportation, Iowa’s radical Republican congress representatives set about legislating freedom. Daniel Stubbs, whose farm was part of the Underground Railroad, authored the resolution to ratify the 13th amendment to abolish slavery. James F. Wilson cosponsored the amendment. On January 31, 1865, it was passed by Congress, but it was not ratified until December 6, 1865.

After the abolition of slavery, however, a set of discriminatory laws called Iowa’s Black Codes persisted. Only white men were allowed to vote. James Yancey was a skilled orator and advocate for universal suffrage. A July 1867 Fairfield Ledger article notes, “A small congregation, numbering about one hundred persons, met in the Park on Monday last, at 3 ½ o’clock, to hear a lecture on universal suffrage, by J. H. Yancey, a colored citizen of our town. Mr. Yancey’s lecture was replete with sound logic and good sense. . . . His plea for the franchise, both for his own race and the women of the country, was a strong one, and was listened to with marked attention.” Ward Lamson was among the enthusiastic listeners.

After James Yancey’s death, Nancy supported the family with a very successful laundry employing five workers and was greatly respected as an entrepreneur. A friend recalled: “All who met her were benefited. Limited in means to the product of her own exertions, she was charitable beyond some who have given millions.”

Nancy Yancey is among those being honored on Monday. Black Civil War veterans Henry Stuart and Robert Winn will also be honored.

Juneteenth 2022 Schedule:

Due to the heat advisory, Carnegie Museum staff will place flags at the graves prior to the celebration. There will be a drive to the cemetery between the presentation and exhibit opening to pay respects. Maps will be provided for those who wish to visit the graves to pay their respects at a cooler time of day.

• 1 p.m.: Underground Railroad in Jefferson County Program, McElhinny House parlor, 300 N. Court Street. Guests will receive a flyer with Underground Railroad graves labeled on a map.

• 2 p.m.: Drive past Evergreen Cemetery to view flag-marked graves

• 2:30 p.m.: Return to Carnegie Museum for Underground Railroad Exhibit unveiling at 3 p.m., 112 S. Court Street. Regular museum hours are Tuesday-Friday 12–4 p.m. and Saturday 11 a.m.–3 p.m.