If you are wondering how to honor Iowa’s Native American history this month, check out Drawn Over: Reclaiming Our Histories, a new exhibition at the University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art in Iowa City. Guest curated by Dr. Jacki Thompson Rand (citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and Associate Vice Chancellor for Native Affairs at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign), this phenomenal exhibition showcases 32 Plains Indian ledger drawings from the Stanley’s collection. Rand and her cohorts have reclaimed these historical images, rescuing them from being seen as antiquated historical footnotes and placing them within the larger living framework of Native American culture, history, and ongoing artistry.

Running through January 2024, this historic exhibition of Plains Indian artwork coincides with Native American Heritage Month, and offers viewers a deeper understanding of the rich artistic and social traditions they come from. Dr. Rand says the exhibition “focuses on the role that the arts have played in Indigenous peoples’ recovery, reproduction, and creation of knowledges that sustain our communities, preserve our history, and decolonize the environments in which we live, work, and create.”

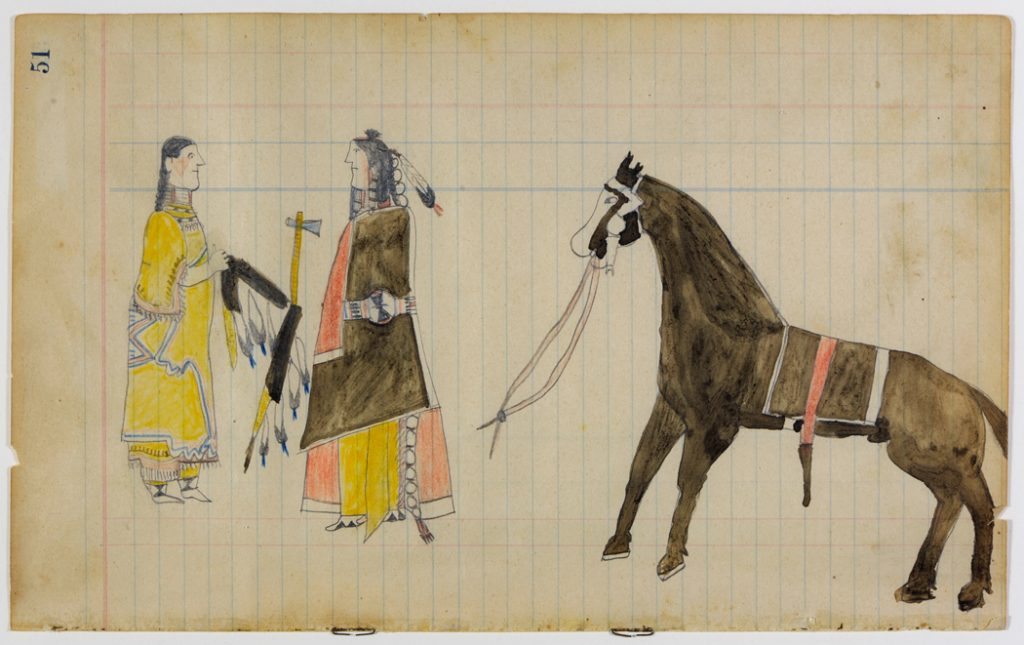

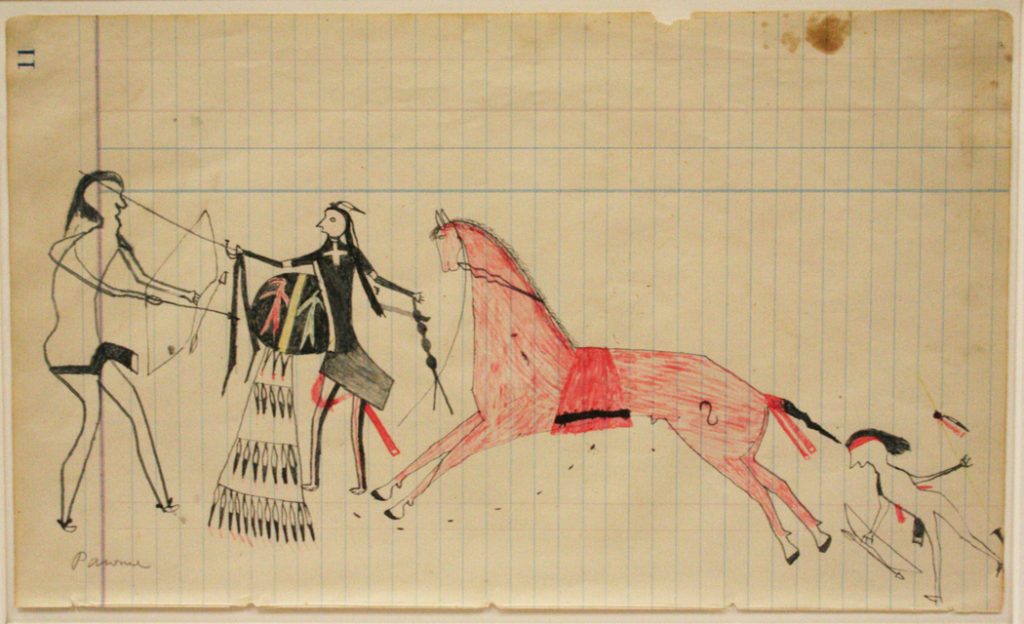

Ledger drawings evolved as an outgrowth of the Plains men’s tradition of hide painting—keeping visual records of tribal stories, achievements, and events on beautifully painted buffalo hides, using a visual language that includes pictographic “name glyphs” and detailed regalia that was easily understood by community viewers. After the U.S. invasion of the Great Plains, the men shifted to using paper from accounting ledgers. This exhibition displays some of the most famous ledger drawings—a selection of pieces created by a group of Plains men who were incarcerated for three years at Ft. Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, from 1875–1878, after the U.S. used accounting ledgers to document them, incorrectly, as criminals. The men were encouraged to sell their work, and ledger drawings became a hot 19th-century art commodity.

Rand organized the exhibition with a cohort of advisors, many of whom are also Indigenous: Erica Prussing (Associate Professor, UI Department of Anthropology, Jennifer New (Community Engagement Specialist), Mary Young Bear (Meskwaki artist), Patricia Trujillo (Ojibwe/Meskwaki retired museum professional), Phillip Round (UI Professor Emeritus, English/Native American and Indigenous Studies).

Stanley Museum Director Lauren Lessing says the way Rand and her colleagues curated the exhibition has been a revelation. “Their focus was so different from what our focus had been when we displayed these ledger drawings in the past,” she explains. “It’s not focused on war. That’s the thing that really struck me—it’s about relationships, and the way that those relationships were imagined and remembered and idealized, at moments when these young men were far away from the people that they loved.”

By focusing on the richly layered aspect of community, the exhibition disrupts stereotypes about Native peoples. Lessing adds enthusiastically that using community as a guiding principle makes the exhibition “tremendously moving.”

No longer positioned as the childlike scrawlings of noble savages from ancient times, the exhibition repositions these ledger drawings as modern art, created by people very aware of the world around them, people who turned to art to deal with the frustrations of unfair incarceration by drawing and painting over the only available material. And while some of the drawings are about war, most of them center on community interactions, with a number of beautiful depictions of courtship rituals. “They drew about themselves,” Rand says, adding a reference to the accounting ledger paper: “They drew over the thing that oppressed them.” It is one of life’s satisfying ironies that the artists repurposed the same accounting ledger paper used to attack their freedoms, using it as the basis of art that showcases the strength of their culture.

At the exhibition opening, Rand noted, “When you stand in this room, we’re not savages. We emerge from this exhibition as complex modern people. We’re an integral part of the history of this country and integral to how the modern world camtogether in this place.”

While Indigenous artists have explored diverse mediums since the 19th century, artists are still making ledger drawings, and some current examples share space with the historic works in this collection, creating context and illustrating that they are very much part of a living and evolving tradition.

Displayed on walls painted “Cheyenne pink,” a color with deep cultural significance, the framed ledger drawings are arranged around the room, with a figurative detail blown up under the exhibition title on the walls. There is a display table showcasing photographs of 19th-century tribeswomen with an example of their beadwork in Cheyenne pink.

A vibrant shade of pink popular with Cheyenne tribeswomen in the 19th century, Cheyenne pink became synonymous with the tribe’s bold, geometrically patterned, intricately crafted beadwork. Since Cheyenne artists created many of the featured ledger drawings, Rand was adamant that the exhibition walls be Cheyenne pink to complement the show and acknowledge their heritage. The exhibition also has musical accompaniment—a recording of piercingly soulful flute music by a contemporary Indigenous musician.

“I hope people come here to enjoy the exhibition to gain a new understanding of Native peoples and Plains Indians culture, but also I hope that people take these ideas and go out and plant them like seeds so that they can grow.”

Admission is free. For more information, visit Stanley Museum of Art.