Delbert McClinton’s been making music his whole life. One thing he’s learned during his 60-plus years in the business is that he keeps getting better at it. That’s no small feat for an artist with his history. He’s won a couple of Grammy Awards and had top-10 singles on both the country and pop charts.

“I think it has something to do with the passion I feel for music,” he said over the phone from his Nashville home. “If I couldn’t express it, I would just explode.” He’ll be performing with his band, the Self-Made Men, at Hoyt Sherman Place in Des Moines on Friday, July 20. They have backed him up for several years and one member, Kevin McKendree (keyboards), has been with him for more than 20.

McClinton’s recorded more than 25 studio albums and several live ones during his career, including 2017’s Prick of the Litter, which went to number two on the U.S. blues charts. He’s had five number one albums on Billboard’s blues charts during the 21st century.

Music has always been a part of McClinton’s life. He said that even as a boy he went around singing all the time. As a teenager he played in and led blues bands in the Fort Worth, Texas, area and accompanied such legends as Jimmy Reed, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Muddy Waters when they came to town. He said he learned something from everyone he played with.

This was during the late 1950s, when many clubs were segregated and black people were treated as second-class citizens. “It was incredibly wrong, and even now I still can’t come to grips with how it ever got that way,” McClinton said with an ache in his voice. “Those guys were my heroes. I can still remember the first time I heard ‘Honest I Do’ [a Jimmy Reed song]. I just lost it. I was driving my car and just had to stop and listen. I had a harmonica and could play simple songs and ditties, but Reed took it to another dimension and got me serious about the instrument.”

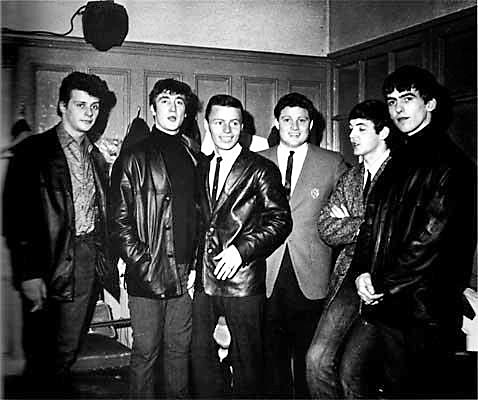

McClinton’s prowess on the harmonica propelled his career to another level. In 1962 he played harmonica on Bruce Channel’s “Hey! Baby.” The song became a number-one hit and led, among other things, to a tour in England accompanying Channel. McClinton mixed with the British artists, met a young John Lennon (they were the same age), and taught him harmonica licks such as the ones on “Love Me Do.” McClinton downplays his influence on Lennon but acknowledges that he has often found himself at the right place at the right time. He has stories about making eye contact with John F. Kennedy before his fatal trip to Dallas, being listed in Jack Ruby’s papers, and living at T. Cullen Davis’s mansion before the murder of Davis’s wife Priscilla—one of the Lone Star State’s most infamous trials.

In fact, McClinton could write a book about his life, and in a sense, he already has. He provided music journalist Diana Finlay Hendrick access to all of his personal journals and submitted to many interviews. The 2017 biography was not authorized per se because McClinton wanted Hendrick to write the story without censorship. His life has not always been well-lived and he admits the ’80s were kind of a blur because of excessive drug use. This is part of the reason McClinton said he keeps on improving—he has learned from his past mistakes.

McClinton said that he has always kept journals and written things on scraps of paper for later use. He mines these for lines or ideas to stimulate him. “I have always found that if you write something down and then revisit it later, you see something you didn’t notice the first time,” he said. McClinton takes pride in his songwriting and takes the process seriously. He also has a strong sense of humor. His best-known songs, such as “Two More Bottles of Wine” successfully covered by Emmylou Harris, have a comic edge.

“How could you live without laughing?” McClinton asked, paused for a moment, and then answered, “It would be impossible!” Although McClinton is often associated with the blues, his are the happy kind. He said his aim is to leave audiences more cheerful than when they entered, and that he writes music as a way of entertaining himself. He doesn’t always keep up with the news and concentrates more on finding what’s good in life.

Yet he’s well aware of the dramatic changes he’s seen during his lifetime. McClinton still keeps the microphone that he bought back in the ’50s for Jimmy Reed when he learned the two would be performing together in Fort Worth. It was one of those big Shure electric units that was almost a foot long and weighed more than a pound. It was only used once. Apparently, Reed got drunk, threw up all over it, and shorted out its crystal components. The memory of it makes McClinton chuckle.

But then he got serious. “I don’t want to disparage Reed. He and other black bluesmen had it rough. They had to stay in segregated hotels and weren’t welcome in many places because of their color. Reed taught me so much, not just about sound, but psychological insights into understanding the world.” McClinton saw Reed’s alcoholism as part of the cost of living in a society that didn’t value people equally.

“I have been lucky,” he said. “I get to do the thing I want to do and have been doing so my whole life. And I know I am a better musician now that I have ever been.”

He wasn’t bragging. He spoke with the confidence of one who takes his art seriously. Critics and fans agree with him. His recordings and performances continue to get rave reviews. “And what was that I said before, if I couldn’t do this I would just explode? Ka-boom!”