Fairfield-based Canadian artist Greg Thatcher has spent almost three decades crafting elaborate drawings and multi-media pieces that explore the surprising beauty of ancient yew trees. An exhibition of his work, entitled Sacred Yews, opens Saturday, February 1, 3-5 p.m., at the Des Moines Botanical Center.

An adjunct faculty member at MIU and part-time teacher at Maharishi School, Greg started his love affair with yew trees in 1991. The paintings he’d been working on were beginning to feel stale and boring. His wife, Jan, suggested going to England, so with an Iowa Arts Council grant, he traveled to Skelmersdale, Lancashire, to work on a printing project with close friend Stephen Whittle, who had a studio there.

A Change of Scenery

During his two months in England, Greg explored the countryside, looking for inspiration. He started out doing obligatory sheep pictures and paging through travel brochures. One brochure had a view of yew trees, with the perspective receding back into space.

“The photograph had been taken on a sunny day,” Greg explains, “so there were these really stark shadows. I looked at it and I noticed that my attention went from where I was sitting into the deep space of the background.”

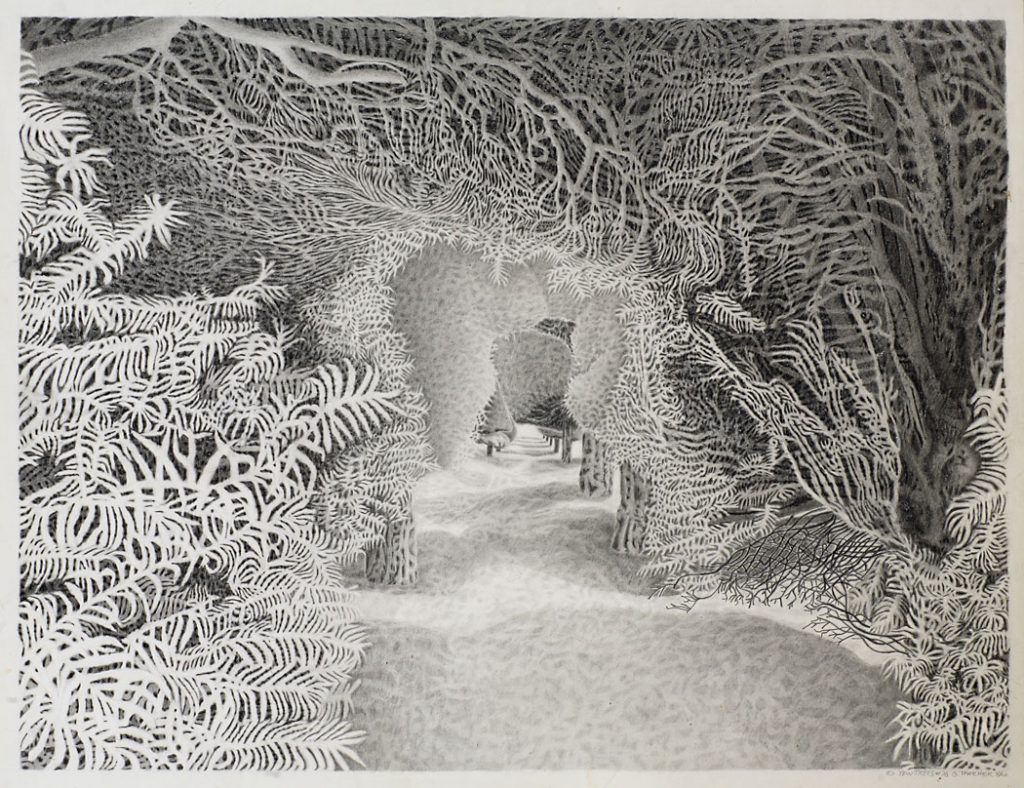

Impressed by the feeling of transcendence this evoked, he decided to explore drawing yew trees. Stopping at St. Mary’s Church in Painswick, he encountered the carefully trimmed topiary yews lining the avenues of the churchyard, and his yew tree series was born. Over 100 trees grace the churchyard in pairs, some having grown together to form archways over the paths. These stately trees, approximately 300 years old, are “gorgeous, absolutely beautiful,” Greg says.

His meticulous drawings mirror the complexity of the yew’s fascinating network of boughs and branches. With a B.F.A. in printmaking from the University of Victoria and an M.A. in drawing and painting from the University of Saskatchewan, Greg had a lot of experience drawing and painting. But the yew trees required an entirely new approach.

“I taught drawing classes and all that,” Greg says, “but when I started on these, I had to throw that all out. I was very lucky to work with Geoffrey Baker. He had a very simple, very clear system for drawing and painting, which I’ve adapted to draw the yew trees.” Baker, a popular art professor at MIU for many years, passed away in 2011.

Disaster Sparks Discovery

Initially, Greg drew the outer shape of the yew trees, but a freak snowstorm in 1997 inspired him to change his focus. Damaged by the weight of extremely wet snow, many trees were later trimmed extensively. He says an avenue of trees about a block long “had been cut back to look like broccoli.”

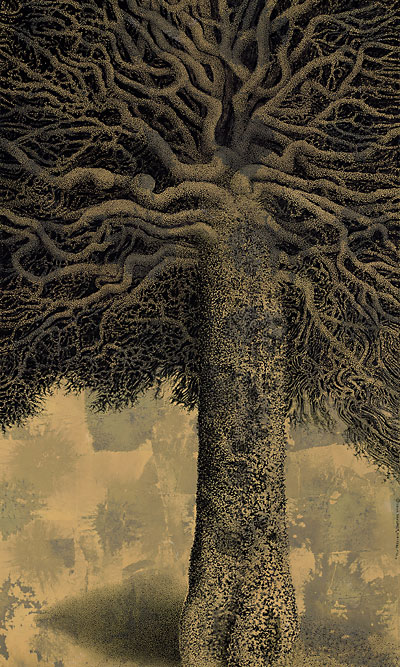

Shocked by the sight, Greg wondered what he could do as an artist “to help build back the sense of purpose or dignity a tree has.” He decided to do a series of drawings focusing on the beauty that the trees still retained. So he began drawing the underside of the canopy, discovering in the process an even richer visual world.

“I went from working on the outside of the trees to the inside of the trees, which is a whole different kettle of fish. The complexity is amplified exponentially when you work underneath.”

The Beauty of Line

Greg still works with the same principles, dealing with positive and negative space and moving the attention from up close to far away. But he puts many more hours into each drawing. His earlier drawings took up to 100 hours each. Those in his current series take anywhere from 450 to 700 hours. He keeps a log on the back of each drawing detailing the dates and hours that went into its creation.

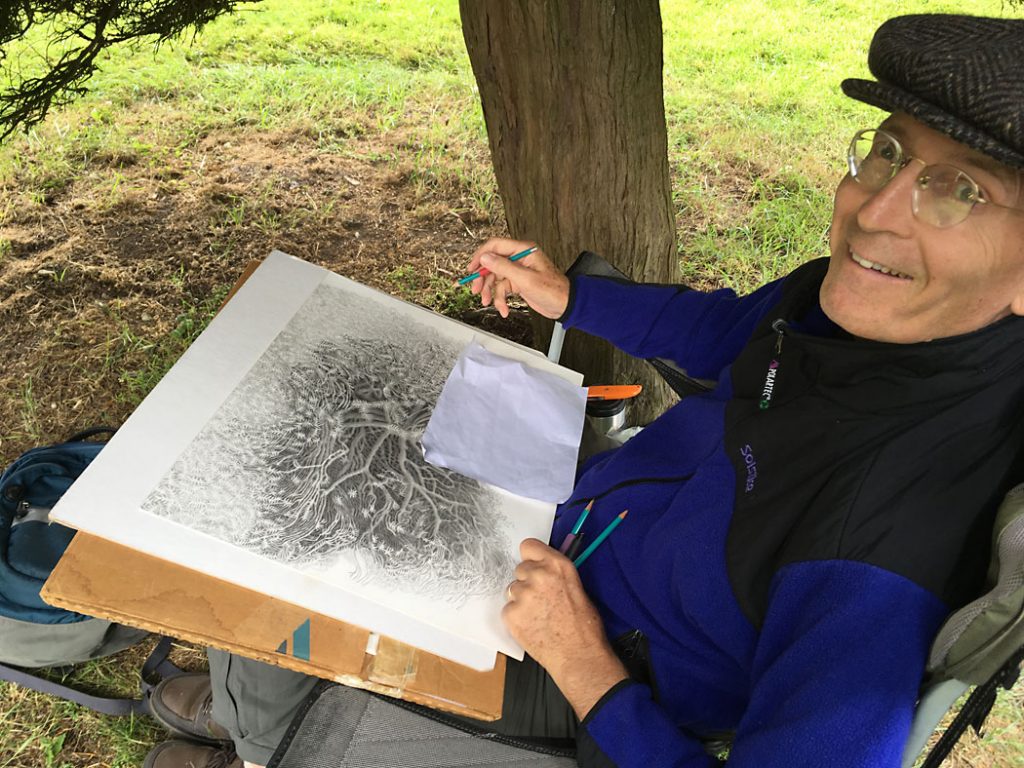

Greg primarily works on site, or “plein air,” and he works every day. More involved pieces might take a month to six weeks. To achieve that extreme level of detail, he takes approximately 170 hours to carefully lay out the placement of tree branches on a grid, paying attention to each line and how everything interacts to form a whole.

His methodical precision with line was influenced by Charlotte Cain, co-founder of the MIU School of Art, who passed away in 2015. She placed enormous emphasis on the beauty of a properly placed line, and insisted that “you need to love everything about your work.” Greg decided this meant more than just liking the way a piece looks: it meant enjoying the rightness and placement of every single line. “Her work was both really dynamic and very silent,” he explains. “Every little line that she would do was purposeful and it had a very specific role that it played within the whole. I applied that same thing here.”

Thatcher uses graphite pencils to create his remarkable yew tree drawings. He discovered that soft ebony pencils made the negative space in the background pop out and separate from the design because their black is too flat. He now uses H, 3H, and 6H pencils, harder pencils with a more silver range, and presses hard to get deeper blacks. This gives his work a greater textural quality, a physicality that makes the visual universe he’s building stronger and more impressive. “The drawing is its own language,” he says, adding that the physicality of pressing hard imbues the drawing with more presence.

Once his black and white drawing is complete, he gets archival prints made by Dale Stephens at ArtFiftyTwo in Fairfield, and then embellishes the prints with colored pencils, acrylics, and metallic leaf.

The Living Trees

Spending so much time delving into the beautiful details of a tree has increased Greg’s awareness of trees as living beings. His art has encouraged a connection with these impressive life forms, and he’s conscious that each tree he draws has its own distinct personality.

“They’re not what we would think about as a cognizant being,” he says, “but they’re alive.” He adds that he feels like he’s their spokesperson. Greg has discovered a number of interesting associations and mythologies about yew trees over the years. Yews were sacred to the druids and believed to ward off evil. Because of their little green leaves and red berries, they were the first Christmas tree.

After spending years sitting with them, Greg feels they radiate a tranquil, coherent energy. “They’re creating this calm, spiritual feeling in the churchyard that’s not necessarily related to the church,” he says. “The church is there, but to me the churchyard belongs to the trees—it’s their ground. So they’re creating this wonderful sort of ambience. If you’re sitting there drawing them, there’s an unseen, constant kind of interaction that goes back and forth between you.” He notes that other visitors to the churchyard notice the settling effect of the yews as well.

Sacred Yews

Greg has exhibited in museums and galleries all over the world, and his work is in both private and corporate collections. For the last two years, he’s had drawings accepted into the prestigous International Drawing Annual, a book distributed to museums, galleries, and universities all over the world.

Sacred Yews, the upcoming exhibition in the North Gallery of the Des Moines Botanical Garden, opens Saturday, January 18, 5–7 p.m. and runs for three months.

For more information, visit GregThatcherGallery.com.