Last month we took a trip into ancient audio history and saw how convenience affected the choices that the electronics industry made, and how these choices affected your stereo sound. The 45 record, spinning faster than the 33 1/3 RPM LP vinyl, should have sounded better than the LP. However, the 45 was designed as a way to sell two songs at a time at a much lower price than the cost of an LP. Nobody tried to make it sound great. They just wanted to sell as many copies of the latest hits as possible.

When the transistor became popular, it immediately took the place of tubes in amplifier design. Solid-state amps, as they were called, could be more powerful for less money, run cooler, and be more reliable. This choice made the industry boom. However, these first transistor amps sounded awful compared to the tube amps they replaced, which were more spacious, smooth, and musical. It took many years for the top transistor-amp designers to come up with designs that could outperform a well-designed tube amp.

For over a decade, tubes were so widely abandoned that it was almost impossible to buy a quality replacement. Eventually, the musical attributes of tube amps inspired a new generation of amplifier designers to switch back. Today, buyers have many excellent choices of tube electronics.

Convenience also took its toll on the recording process. When professional multi-channel, reel-to-reel tape recorders came into widespread use, it became more convenient to record one section of an orchestra in a small recording studio than to gather all of the musicians together in one large concert hall. The spacious acoustics of the hall were lost, so engineers had to add artificial reverberation. The famous label Deutsche Grammophon would still record the Berlin Philharmonic in their large concert hall, but they used so many microphones that it decimated the room acoustics anyway. This great musical institution, world-renowned for their luscious strings, sounded harsh on those recordings.

One thing that can be said in defense of multi-channel recording is that it gives the engineer a way to correct a poorly executed passage. I remember a story about a famous pianist who asked his equally famous colleague to listen to his recently finished recording.

“Isn’t it beautiful?” the pianist asked his colleague. And indeed, it was perfectly performed and captured.

“Yes, it is,” his colleague replied. “Don’t you wish you could do that?”

The recording had been created by editing and splicing together many less-than-perfect takes. Personally, I still like a live performance, recorded in the right venue with two simple mics, full of natural room acoustics, one take, warts and all. It captures an intensity and continuity of emotion that is rarely preserved using multiple takes.

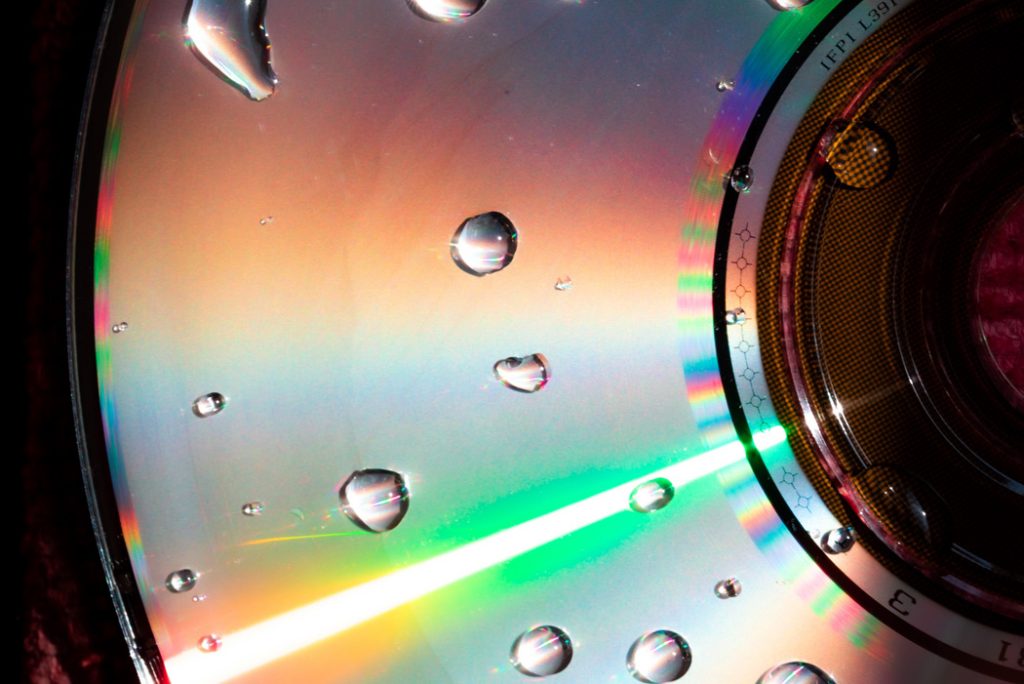

In 1982, after a few years of trying to fit the new digital recordings onto analog vinyl LP records, Sony and Philips co-created a new format for digital music, the compact disc. Its small size, cool shape, and increased playback time made it an instant hit. They marketed it as “perfect sound forever.” Early demos would always include the presenter dropping the CD on the floor and stepping on it to prove its ruggedness. We soon learned that it wasn’t quite that rugged. Also, it didn’t sound nearly as good as our best LPs. Early CDs had great bass and low noise, but they sounded bright and harsh. Nevertheless, their convenience inspired clients to dump their record collections and replace them with space-saving CDs. Today’s current move back to LPs was in no small way fueled by the availability of those low-priced abandoned records.

Fortunately, CD brightness became a challenge to audio designers. One of the first audiophile CD players was outfitted with tube preamplifiers to smooth out the roughness. CDs and digital recording were still in their infancy, and some very good minds decided to tackle the problems, certain that CDs should sound much better than they did.

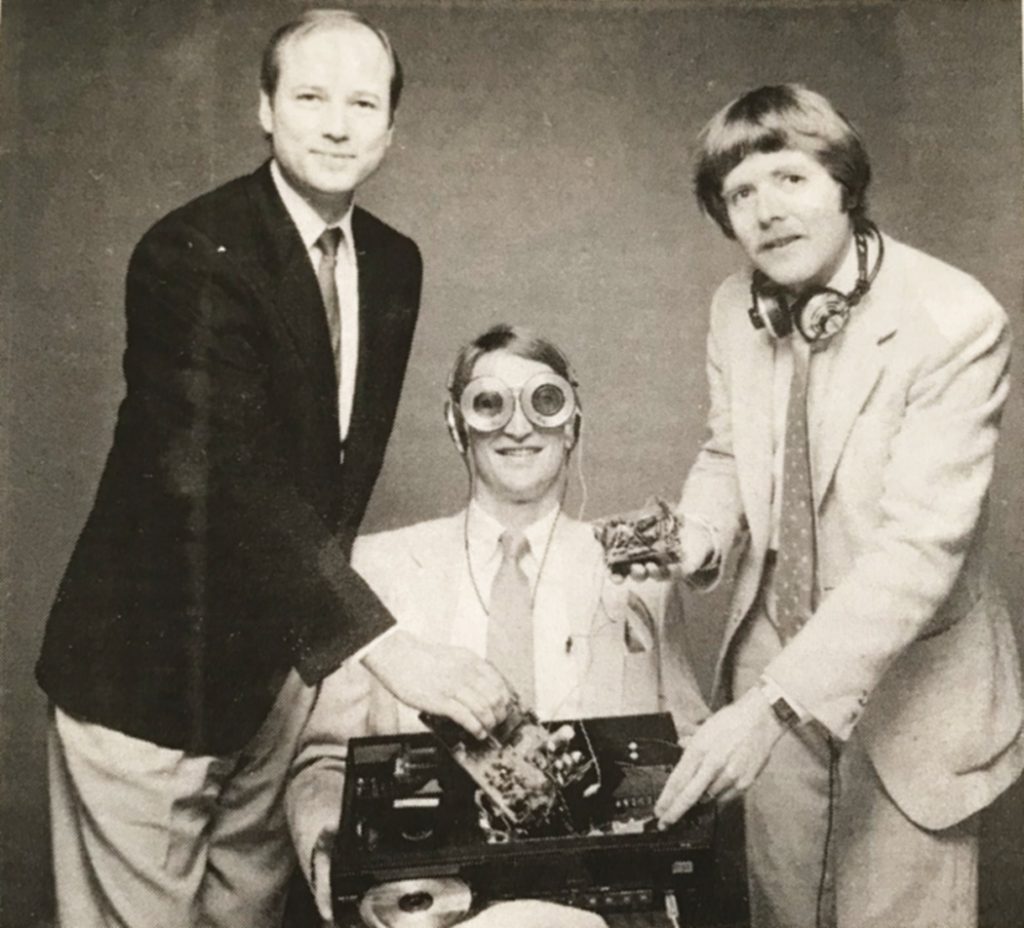

It took a couple of MIU faculty members here in Fairfield to make some of the biggest breakthroughs in understanding this new thing called digital music recording. Digital wizard Alistair Roxburgh and theoretical physicist John Hagelin started Enlightened Audio Designs (EAD), a company that became known for producing some of the most musical CD players and digital-to-analog converters in the world.

As it turned out, all of those early digital recordings had serious timing problems, both on the disc itself, and in the CD player. Once EAD (and soon after, a number of other high-end manufacturers) corrected these time issues, the CD became an excellent source for music. We finally had convenience and performance in the same place. By then CDs could play in your personal portable and your car, with minimum sonic compromise.

Of course, CDs eventually morphed into DVDs, which finally gave us the first high-quality standard-definition videos for our homes. DVD-Audio and SACD discs were introduced to show us much higher quality audio than the CD, then Blu-ray and 4K Blu-ray raised our picture and sound to incredible performance levels.

After over three decades of this wonderful CD format, and some good years of DVD and Blu-ray, “progress” again reared its head. The music and video industries bet on the ability to broadcast music, and suddenly, we jumped all the way back to the beginning of my story. Like with the old 45 records, created cheaply for maximum sales, the industry was willing to produce music on MP3 files that threw away most of music’s subtlety. Vastly inferior to the sound of a good CD, this “convenience” set us back musically by 20 years!

Fortunately, some of the streaming and music downloading services brought the quality back. Now we can get our online music to exceed the performance of CDs from forward-thinking companies like Qobuz and Tidal. Of course, the discs with video are now capable of superb picture quality. Unfortunately, streamed sound is still a bit of an afterthought to most video engineers; it rarely compares with the sound quality on a disc.

Today, sales for all types of discs have dropped dramatically due to the convenience of streaming. Ironically, in the past year, so many of the people who got into vinyl to feast on all those abandoned LPs are now buying more new, well-pressed LPs than CDs. Talk about going full circle!

I find it somewhat satisfying that for the love of music, so many have gone retro to the least convenient format of them all, the record player. Is it the best choice musically? Let’s save the digital versus analog issue for a future column.

Paul Squillo is CEO of Golden Ears Audio in Fairfield, Iowa.