As a high school student in Iowa, I was an avid follower of MAD Magazine. I also subscribed to the Village Voice. Concerned about my waywardness, my mother arranged for me to meet with a religious elder for an advisory conversation. I was a youthful artist then, and during that meeting the subject turned to visual art. The sagacious elder said to me that only that morning, he had read an editorial in the Wall Street Journal that claimed, “Modern Art is a dung heap.”

Moments later, I was somewhat put at ease when he laughed goodnaturedly and said that there was no reason for anyone to worry about me—I was simply going through a phase. Most likely, the source of my problem, he said, was that I was reading “too much MAD Magazine.” Out of politeness, I didn’t respond. But in my mind I wondered if the source of his problem was that he was reading “too much Wall Street Journal.”

I recall that a further concern was my newfound interest in the Beat Generation and in writers referred to as “beatniks.” A few years earlier, a former football player from Lowell, Massachusetts, named Jack Kerouac had published a rambling, unorthodox novel called On the Road. Among my chief interests was literature, controversial or not. I had first read Kerouac’s book around 1962, including that now-famous passage in which he lamented having traveled through Iowa too quickly—“past the pretty girls, and the prettiest girls in the world live in Des Moines.”

When On the Road was first released in 1957, reactions from critics were radically mixed. As its notability spread, so did the fame of its author, who soon became known as the King of the Beats. His book was a pivotal influence on a generation of writers, musicians, and others, among them the Beatles, David Bowie, Bob Dylan, and Jim Morrison.

Debate about Kerouac’s novel increased exponentially when it was revealed that the book had been typed on a continuous 120-foot scroll of tracing paper, single-spaced, with no paragraph breaks, much less breaks for chapters. The author referred to this approach as “spontaneous prose,” but Truman Capote was unconvinced. What Kerouac does, said Capote, “is not writing—it’s typing.”

Concurrent with this, another leading figure in the Beat Generation, a New York poet named Allen Ginsberg, had published a lengthy protest poem called “Howl.” Initially banned as being obscene, it was cleared in a famous court case in 1957, the year that On the Road came out. This was followed two years later by William S. Burrough’s The Naked Lunch, also con-demned as being obscene, and this trinity of infamy—Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs—became widely recognized as the “beatific” echelon. To my memory, the most enduring of the three was Ginsberg, partly because of the fact that in the spring of 1968, when I was an undergraduate at the State College of Iowa (now the University of Northern Iowa), he was invited to visit the campus for three days.

To understand why Ginsberg was of interest to myself and other students at the time, it is important to realize that public protests against the Vietnam War were occuring nationwide. He had been invited to speak on numerous campuses and was widely recognized as one of the war’s most virulent critics.

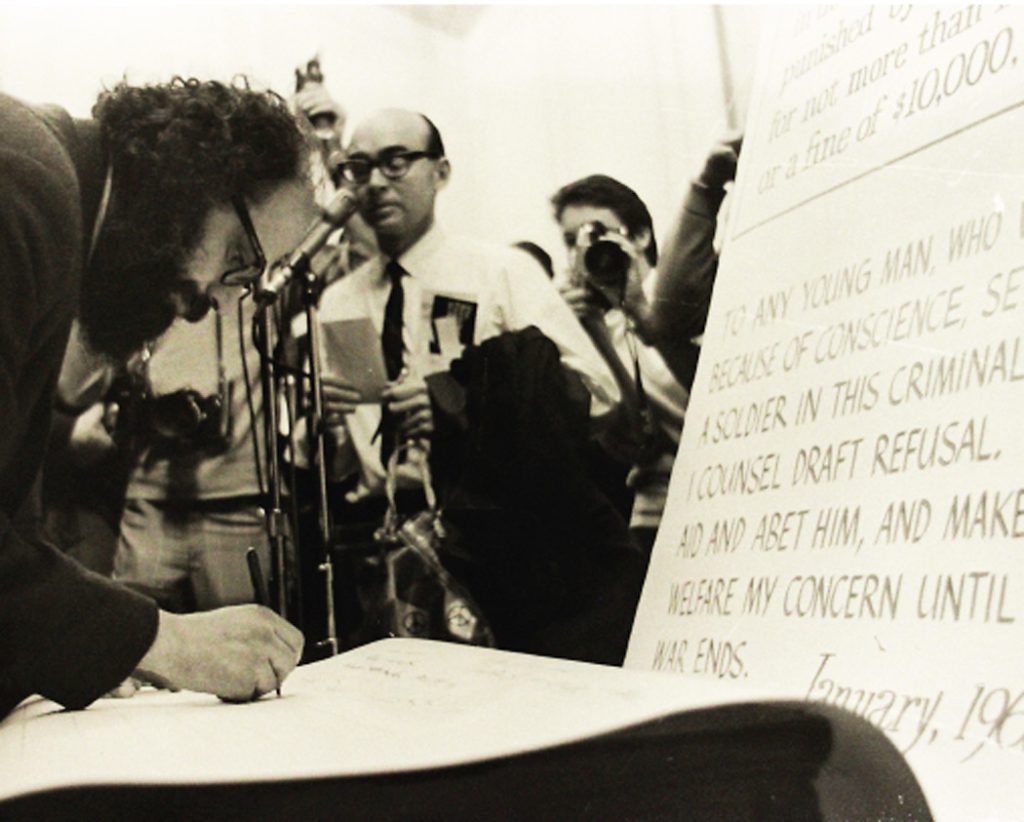

The campus at Cedar Falls was especially poised for a rally by a rousing war opponent. Only a few months earlier, one of the school’s English professors had publicly burned his draft card. In response, there was an outcry from community “patriots,” demanding that the school’s president, J.W. Maucker, should fire the protesting teacher. And if Maucker failed in doing that, then he himself should be dismissed. Among students, there was a remarkable show of support for Maucker’s defense of due process and freedom of speech, including opposing the Vietnam War. The degree of support is confirmed by a clipping from the Des Moines Register (dated October 21, 1967) in which there is a photograph of myself holding a petition for students to sign. The news article states that an estimated 5,000 students signed that document during a rally one evening. We then marched to Maucker’s home, to stand in vigil throughout the night.

Another less evident factor was that the country was still in the process of healing its self-inflicted wounds from the so-called American “Red Scare,” an anti-Communist witch hunt that had been spearheaded by Wisconsin senator Joseph McCarthy from 1947 to 1957. Not only did McCarthy seek to “out” Communists, Socialists, or simply political liberals, he also ran a side campaign, known as the “Lavender Scare,” in which he and others searched for government employees who were gay, for the purpose of demanding that they be terminated. As a result, Ginsberg had multiple reasons for speaking out against demagogues, since he himself was openly gay. In addition, his mother, a Russian-Jewish émigré, had been an active Marxist who sometimes took her sons along when she attended political meetings. Following a breakdown, she was institutionalized for mental illness, including the “delusion” that the FBI was watching her—which was most likely well-founded.

In the days before his appearance in Cedar Falls, Ginsberg had spoken in Appleton, Wisconsin, at Lawrence University. His Wisconsin visit made national news, because Appleton was Joe McCarthy’s hometown, and before leaving town, he and his followers gathered at McCarthy’s grave, where they performed what they described as a ceremonial exorcism to release McCarthy’s demons.

Arriving at the Waterloo airport, Ginsberg spoke at a press conference. He was then escorted to campus, where for the next few days he spoke publicly, performed at poetry readings, and visited on-going classes. Among those classes was a drawing class in the Arts and Industries Building, in which I was a student. He had a great full beard, and the drawing instructor suggested that Ginsberg simply sit on a chair on a platform, so that the students could draw him. I did this for a few minutes, but it soon occurred to me that I was missing an opportunity. So I suddenly stood up, walked over to him, sat on the floor in front of him, and the two of us began to talk. I recall almost nothing of our conversation, except for one vivid exception: I remember that he told me about having recently made a film beneath the Brooklyn Bridge, in which the major performers were Irish playwright Samuel Beckett and American film comedian Buster Keaton.

I saw him later a couple of times, but I remember almost no details. I attended an evening party, organized by students, that was held in a large historic building called “Fourth and Main” in downtown Cedar Falls. It was extremely crowded. There was a less dense gathering at an off-campus coffee house, during which Ginsberg chanted as he accompanied himself with a small, red box-like accordion.

My final, most lasting memory is that of being in the audience when he gave a major reading in the auditorium of what is now Lang Hall. I was seated in the balcony, where I had an excellent view. The highlight of the evening came when he read one of his most compelling works, “Wichita Vortex Sutra,” in a forceful, rhythmic voice. Written in 1966, it was a poem about the Vietnam War that he had composed while traveling through Kansas on a bus.

Whenever I think of that reading by Ginsberg, it inevitably brings to mind an earlier, equally powerful talk that I had attended one year earlier—in the same auditorium. It was one of the last public lectures by an old charismatic champion of freedom of speech, American Socialist Norman Thomas. He was in his early 80s and all but impossibly hampered by old age, arthritis, and declining vision. In advance of his speech, it appeared that they might have to carry him to the front, and prop up his arms on the lectern. But once so positioned, a powerful, clarion voice broke out and took command of all the seats.

Norman Thomas soon retired from public life. He died in late 1968 at age 86, just a few months after Ginsberg’s talk. As a perennial candidate for the U.S. Presidency, this tall, handsome, courageous hero had always been well-spoken and known for his witty rejoinders. While agreeing that he was encouraged to see a new generation of outspoken youth—alluding to beatniks and others—he said, “I just wish they’d cut their hair.”

In the year that followed Ginsberg’s Iowa visit, Roy R. Behrens graduated from college and taught in a public high school. A month before the end of the school year, he was “selectively serviced” and inducted into the U.S. Marine Corps. Nearly two years later, having attained the rank of Sergeant, he was honorably discharged, and went on to become a university professor.

For more information, see Bobolinkbooks.com/ballast.