A new show featuring Japanese prints from the 20th century to the present opens at ICON Gallery in Fairfield during First Fridays on August 5. The exhibition draws upon the collections of several Fairfield residents, along with an important loan of works from the Grinnell College Museum of Art.

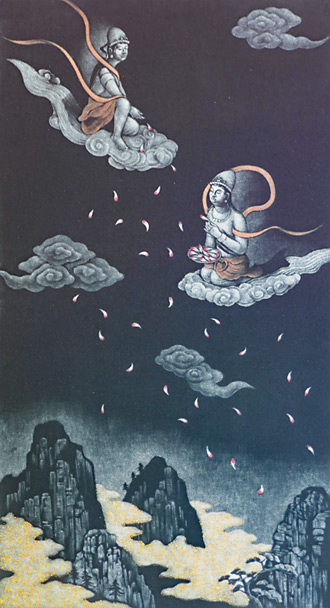

Modern Japanese Prints will showcase more than 40 artists and close to 100 works, mostly from the 1950s to the present. A wide variety of print media is represented, including woodblock, etching, mezzotint, stencil, and silkscreen. The subject matter encompasses everything from still life and landscape to abstract and imaginative works.

Japanese Influence on Western Art

Beginning in the 1850s, after over two centuries of self-imposed isolation, Japan established diplomatic and trade relations with many nations. Among the goods that began to flow to the West were ceramics, lacquerware, textiles, decorative objects, and woodblock prints. Japan’s pavilions at the World’s Fairs in London in 1857 and Paris in 1862 fueled a European mania for all things Japanese, a trend known as Japonisme.

Japanese art had a marked influence on the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists in France in the late 1800s, many of whom became ardent collectors of Japanese woodblock prints. These prints, known as ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world,” depicted subjects such as historical and mythological tales, popular kabuki theater actors, geishas, and travel scenes. Collectors included artists such as Claude Monet, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Vincent van Gogh, all of whom incorporated aspects of Japanese art in both their subject matter and artistic devices.

Western Influence on Japanese Art

This cultural exchange also resulted in a reciprocal influence of Western artistic styles and methods upon Japanese artists. With travel restrictions removed, some Japanese artists traveled in the late 1800s to Paris and other cities to study. Upon their return, they practiced and taught the styles and techniques they had acquired there.

The Western style of painting, known as yōga, was subsequently incorporated into the curriculum of fine arts schools in Tokyo and elsewhere. But there was also pushback by artists who wished to maintain the unique traditions of Japanese art. Their style, known as nihonga, was more selective in its adoption of European techniques. The result was a synthesis of Japanese and Western styles, as both schools came to be accepted on equal footing.

The Emergence of the Printmaker as Independent Artist

Throughout the 19th century, ukiyo-e prints had a second-class status in Japan. They were a popular medium that could be acquired inexpensively by the middle class to decorate their homes, but were not considered to be “fine art.”

Historically, the woodblock print was a cooperative process, controlled by well-established publishing houses, in which each step of making a print was delegated to a different class of artisan. The publisher selected an artist to sketch the image, often based on what was expected to be popular. Next, a designer would create drawings for the different blocks that needed to be carved for each layer of color. Once the drawings were transferred to the blocks, skilled carvers prepared them for printing by experts in that craft. The final print would then reach buyers through the publisher’s retail channels.

Starting in the early 1900s, some artists began to promote the notion that the artist should be the sole creator of all stages of a print, from conception and drawing to carving and printing. This movement, known sōsaku-hanga, or “creative prints,” marked the start of the ascendancy of woodblock prints to the realm of “serious” art. The print became a complete, personal expression of the individual artist, rather than the result of an artisanal production process. Some sōsaku-hanga artists proudly emphasized this distinction by labeling the backs of their prints with the phrase “Self-Designed, Self-Carved, Self-Printed.”

Meanwhile, a parallel school, known as shin-hanga or “new prints,” continued with the collaborative system of print production, with many of the same themes as ukiyo-e, but with a modernized approach to color, light, shadow, and mood. The primary market for shin-hanga was in the West, where the prints were very popular. Within Japan itself, however, their style was considered to be outdated and had limited appeal.

The Post-War Era and Popularity of Modern Prints in the West

In the 1920s and 1930s, young people in Japan enthusiastically embraced jazz, café society, and Western clothing and hairstyles, and these modern tastes were reflected in the visual arts as well. However, with the rise of Japanese militarism in the 1930s and the eventual alliance with Germany in World War II, images supporting the war effort were officially favored, while Japanese avant-garde artists had a diminished status.

Japan’s defeat in the war, ironically, proved to be a huge boon to the sōsaku-hanga art movement. From 1945 to 1952, nearly one million Allied troops and their families occupied the country as Japan transitioned to democracy. The modern prints proved to be extremely popular with U.S. servicemen and -women and were purchased in large numbers as souvenirs, thus enabling many sōsaku-hanga artists to support themselves from their art alone. The resulting flood of Japanese prints arriving in the United States exposed thousands more to this unique art form, and its popularity with collectors continues to thrive today.

ICON Gallery is located at 58 N. Main St. in Fairfield.