Every day, Iowans drive past 19-century storefronts and factories, square farmhouses, and the occasional one-room schoolhouse or chapel. To Terry Philips and Sandra Johnson, what we do with these centenarian structures speaks volumes about who we are as a society. “There is no building as green as the one that already exists,” Sandra tells me. “In one word, it’s sustainability.”

It’s a sentiment that has been echoed and paraphrased by architects and preservationists. Many understand the concept of embodied energy—the energy it takes to harvest resources, process them, and manufacture something new. But few realize exactly what that means for Iowa’s centenarian structures, from their raw materials to their economic and social value. Terry and Sandra are on a mission to change that, and Mills Seed Company is their headquarters.

Mills Seed Company

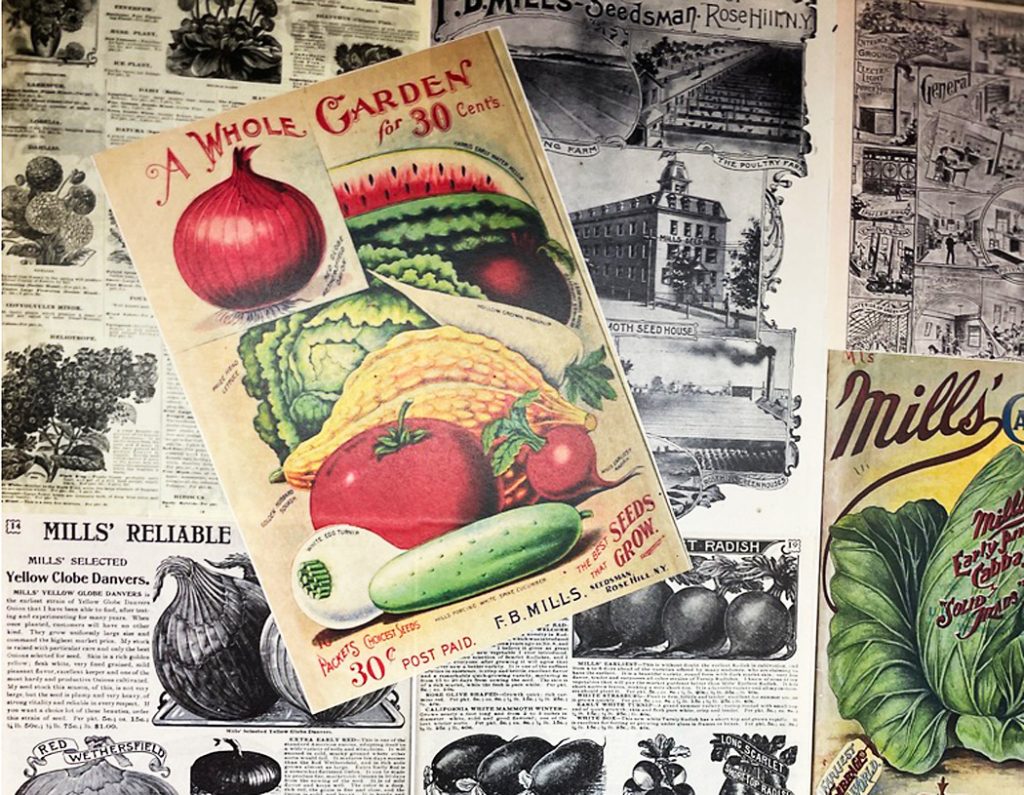

The 1907 Mills Seed Company building in Washington, Iowa, is constructed of classic, cheerful warm red brick. With three stories sunlit by tall windows and a full basement below, there’s plenty of space to house its past, present, and future. The building is part gathering room for musicians and speakers, part retail space for antiques and pop-up makers. It serves as a warehouse for salvaged lumber and building materials, and a workshop where Terry repairs windows. The third floor is full of relics from Mills Seed Company’s past lives as a seed distribution center, printing company, and button-card factory, with its collection of seed catalogs, valentines, tally cards, and assorted buttons.

Sandy and Terry are fond of the building’s original open layout. “To me, community is not just outside the building, it’s also inside a building,” Sandra explains. “You feel different when you enter architecture that lifts you up, which is what the tall ceilings and unobstructed pathways do. Because it opens. It opens you up to community when you aren’t isolated. That space often makes you feel elevated and optimistic and worthwhile.”

Even so, the Mills Seed building has had its own close calls and controversies. It was once considered an eyesore—something difficult to imagine today with its lovingly landscaped entryway and tidy path to the front door. In a real sense, Terry and Sandra rescued the building, and rescuing buildings—and in some cases, their parts—is Terry’s specialty.

Deconstruction

“Everyone knows what demolition is,” Terry explains. “You tear something down. A building that has reached the end of its life cycle gets destroyed, hauled off, burned, or whatever. Deconstruction is taking it apart.”

Terry and Sandra have salvaged all kinds of parts from deconstruction projects: floorboards, joists, siding, plumbing fixtures, window sashes, doors, even square nails. These materials can then be used in restoration projects, or even in new buildings. The most precious material is old-growth lumber harvested in the 1800s and ferried downriver to Iowa’s sawmills.

The trees in the old-growth forest were typically over a hundred years old, sometimes several centuries old. Modern lumber comes from young, fast-growing trees, only 30–40 years old. “We think [old-growth lumber] doesn’t exist anymore,” Terry says conspiratorially. “But it actually does exist in these buildings! The value of this old-growth material is that it’s stronger, it resists rot, and resists insects. It’s just phenomenal.”

But most of the time, buildings made of old-growth lumber are abandoned, burned, or razed and added to an expanding landfill. “The energy in a razed building is something that should be lamented when it is lost,” Sandra tells me.

Terry agrees. “We can’t simply go on the way we’ve been doing, tearing the forests down and going on to another frontier. Climate change is real. Saving materials is more about saving the energy, because the sawmills that ran to cut these logs are long since gone. But all that energy was used and carbon has been captured by other trees. If we cut down more trees, we extend our carbon footprint.”

Built to Last

Cradle-to-cradle design is the idea that humans can and should design for perpetual repair, reuse, and finally deconstruction into raw materials. “When the people built these buildings 100 years ago, they built them to last 200 or 300 years. That was the philosophy they had; that was their mindset,” Terry says. Then he grins. “It is so much fun to enjoy the craftsmanship of a guy that was doing this 100 years ago. He needed a paycheck. But he knew full well that what he was doing was going to last and he wanted to make sure that he did it right. Didn’t cut corners. And you can see that in all the details of what he did.”

That attention to detail is visible in the triple-layered brick walls of Mills Seed Company, still perfectly aligned. Stairways have decorative wedges in every corner to make sweeping easier. But the building went up fast. Construction began in June of 1907. By September, it was open, and by December, they were operating.

In the Mills Seed workshop, Terry shows me some window sashes he’s working on, pointing out the grooves and the stainless steel pins that hold the original glass in place, and noting how added weather stripping can make the window as weatherproof as its modern-day counterparts. “They never used glue. Because glue made it difficult to make the repairs.” Terry estimates his refurbished windows will last another 100 years, when someone else can take them apart to maintain them.

In contrast, he says new windows will last 30 to 40 years. Glue and vinyl are pervasive in new construction. That limits potential for repairs and destines them for the landfill. The petroleum-based materials also off-gas, with the potential for creating toxic fumes and structural hazards if they melt in a fire.

The ingenuity of the past isn’t limited to repair. Old-fashioned approaches to passive energy could help reduce modern electric bills. Terry shows me the favorite window from his childhood home in Stockport. It’s about as tall as he is, an arched window framed in white wood that still opens and closes. It sometimes goes on tour to preservation conferences.

“The sashes in older buildings are designed to raise the lower sash up about a third of the way and lower the top sash a third of the way in the summertime. You’ll get a natural convection of cool air coming in the bottom, warmer air going out of the top. People think it must’ve been unbearable to live in those houses without air conditioning. Well, that wasn’t a real problem, because you can open those windows up in the evening when the cool air is out there, and close them in the morning. It was really easy to maintain the temperature.”

Community

The Mills Seed building was nearly razed a century after it was built. Unoccupied and in need of roof and window repairs, it became a target of vandalism. In 2009, locals got it on the 10 most endangered buildings in Iowa list. That’s when Terry met the building, so to speak. In January and February of 2010, the previous owner hired Terry to replace mortar and prepare the building for its move across the railroad tracks from light industrial to commercial zoning.

Many buildings with a century or more of life left in them fall out of use because the needs of the communities around them change, and zoning doesn’t catch up. “To be so black and white about zoning makes a checkered pattern out of your city, and that isn’t the way people in my opinion should live,” Sandra says. She was mayor at the time many residents complained about Mills Seed. “You need to understand your neighbors’ needs and be conducive to that. But if you want a community, a thriving community, you have mixed use.”

Sandra believes that zoning, imagination, and government incentives are all crucial for the futures of our cities. She’s troubled that former schools and factories are razed instead of being adapted to serve pressing needs for affordable housing and affordable offices for start-up businesses.

“They’ll incentivize new construction,” she notes of many city councils. “They’ll put all kinds of tax incentives and maybe some startup funds and maybe even some micro loans or more to help construction that has no embedded energy in it to recover. But they don’t find value in investing in, or even allowing, an under-utilized building or a gray zone to come back into full utilization.” The consequence is housing developments that require new infrastructure—roads, plumbing, electricity. They seldom meet the need for affordable housing, typically use unsustainable newly manufactured materials, and consume agricultural land.

“Infill is an opportunity.” Sandra explains that when communities incentivize restoration of existing buildings, or even building on empty lots, the infrastructure is already there. The embodied energy and long-term maintenance costs are already accounted for. “Why wouldn’t a city council put a modicum of investment into that space? If you need a certain classification, worker housing or low- and moderate-income housing, incentivize the construction that meets your community needs versus incentivizing a developer.” It’s far more cost effective to adapt the use of a building than to demolish it when you consider the costs of embodied energy in the construction and materials.

Inviting a Sustainable Future

“How do we begin to change our society from the throwaway generation to the invest-in-your-future-community generation?” Sandra asks. She’s been called a tree hugger for posing those kinds of questions. But that doesn’t stop her from contacting the Public Library to organize Earth Day activities for the kids to share the joys of upcycling and gardening. She’s inviting local vendors who repurpose materials in creative ways to have booths at Seed Mills for Earth Day weekend, which coincides with Southeast Iowa Roadtrip and draws shoppers from across the region who want to find something antique, or at least barnyard chic.

Sandra and Terry both describe themselves as “placeholders” for the Mills Seed building. They hope their efforts enable several future generations to utilize the space.

In the meantime, the Mills Seed Co. Building Facebook page is always bustling with their latest restoration projects and community events. Every third Tuesday from 4:30–6:00 p.m., they host Southeast Iowa Venture Club to welcome and encourage creative people who want to start or grow a business. Terry mentors people who are interested in the arts of historic preservation, and teaches free workshops for passive wood-floor restoration and window refurbishing. Artists have pop-ups. One presidential candidate drew more than a hundred people. Musicians regularly play on the tiny stage.

“What artists like best about that space, it’s not just about the acoustics, it’s that people come just to hear the music. It’s not necessarily to socialize, although we certainly encourage that. The music joins the audience one to another. It’s a personal event, a personal satisfaction you get from hearing that artist express themselves in such an intimate way that a large venue does not provide. It’s not a bar scene. It’s not an auditorium. It’s just sit and listen and enjoy every note.” Dan Henderson nicknamed it “the homegrown series,” and it attracts performers from across the state as well as locals.

Visitors Welcome

Every time I stop by Mills Seed Co., the furniture is arranged differently. The music venue shapeshifts to accommodate vendors, shop displays, and community gatherings, all overseen by vintage prints of vegetables and valentines. Visitors are welcome to see the latest arrangement and peruse old tally cards, Campbell’s soup mugs, and all manner of antiques 10 a.m.–3 p.m. every Saturday. To shop or visit at other times, or to perform or inquire about a vendor booth, check the Facebook page or give Terry a call at (319) 430-8536. Volunteers for Earth Day library activities Friday, April 21, 2023, are also welcome.