EDITOR’S NOTE: Homegrown National Park is the brilliant idea of Doug Tallamy and Michelle Alfandari to restore biodiversity by planting native species in our yards. They call it “the largest cooperative conservation project ever conceived or attempted.” Simply stated, the small efforts by many of us to add native plants and habitats to our properties can provide new ecological networks in which wild things—everything from insects to mammals—can survive and flourish.

In this excerpt from his online blog, “Garden of Life,” Tallamy explains why it’s so important to support our insect and bird populations with native plantings.

Chances are, you’ve never thought of your garden as a wildlife preserve that represents the last opportunity we have for sustaining plants and animals that were once common throughout the U.S. But that is exactly the role that built landscapes are now playing— and will play even more in the near future.

If this is news to you, it’s not your fault. We were taught from childhood that plants are decorations and our landscapes are for beauty. But no one has taught us that we have forced the plants and animals that evolved in North America (our nation’s biodiversity) to depend more and more on human-dominated landscapes for their continued existence. We have always thought that biodiversity was happy somewhere “out there, in nature,” in a local woodlot or perhaps our state and national parks. We have heard little about the rate at which species are disappearing from our towns. Even worse, we have never been taught how vital biodiversity is for our own well-being.

We Have Taken It All

The population of the U.S. is now over 330 million people, fueling unprecedented development that continues to increase over 2 million additional acres per year (the size of Yellowstone National Park). So far, we have planted over 62,500 square miles—some 40 million acres—in lawn.

To nature lovers, these are horrifying statistics. I stress them so that we can clearly understand the challenge before us. We humans have taken 95 percent of the natural world and made it unnatural.

But does this matter? Absolutely, both for biodiversity and for us. Our fellow creatures need food and shelter to survive and reproduce, and we need robust populations of our fellow creatures because they are what run the ecosystems on which we all depend.

Why We Need Biodiversity

Biodiversity losses are a clear sign that our own life-support systems are failing. It is plants that generate oxygen and clean water, that create topsoil out of rock, and that buffer extreme weather like droughts and floods. It is insect decomposers that drive the nutrient cycles on earth, allowing each new generation of plants and animals to exist. It is pollinators that are essential to the continued existence of 80 percent of all plants, and it is birds and mammals that disperse the seeds of those plants and provide them with pest control services.

And now, with human-induced climate change threatening the planet, it is plants that will suck much of that excess carbon out of the air, build their tissues with it, and pump the surplus into the soil for long-term storage—if we would only put them back into our landscapes. Humans cannot live as the only species on this planet because it is other species that create the ecosystem services essential to us. Biodiversity is not optional.

Parks Are Not Enough

I am often asked why the habitats we have preserved within our park system are not enough to save most species from extinction. Years of research by evolutionary biologists have shown that the area required to sustain biodiversity is pretty much the same as the area required to generate it in the first place.

The good news is that extinction takes a while, so if we start sharing our landscapes with other living things, we should be able to save much of the biodiversity that still exists.

Plant Choice Matters

What will it take to give our local animals what they need to survive and reproduce on our properties? Native plants—and lots of them. This is a scientific fact deduced from thousands of studies about how energy moves through food webs.

The general reasoning goes something like this: All animals get their energy directly from plants, or by eating something that has already eaten a plant. The group of animals most responsible for passing energy from plants to the animals that can’t eat plants is insects. This is what makes insects such vital components of healthy ecosystems. So many animals depend on insects for food (e.g., spiders, reptiles and amphibians, rodents, 96 percent of all terrestrial birds) that removing insects from a food web spells its doom.

But that is exactly what we are doing in our landscapes. For over a century we have favored ornamental plants from Asia, Europe, and South America over those that have evolved right here. If all plants were created equal, that would be fine. But every plant species protects its leaves with a species-specific mixture of nasty chemicals. With few exceptions, only insect species that have shared a long evolutionary history with a particular plant lineage have developed the physiological adaptations required to digest the chemicals in their host’s leaves. They have specialized over time to eat only the plants sharing those particular chemicals.

My research has shown that non-native ornamentals support 29 times less animal diversity than do native ornamentals. And when these same ornamentals escape our gardens and run amok in our natural areas, they reduce insect biomass by 96 percent.

In the past, we designed landscapes as if they weren’t essential parts of our local ecosystems. But if all the places in which we live, work, and play are excused from contributing to our local ecosystems, then the natural world that supports us is whittled down to nonfunctional remnants of its former self.

Everyone who owns land has a golden opportunity to enhance local ecosystems by including ecological function as a criterion when choosing landscape plants. And everyone who does not own land can become a player in the future of conservation by volunteering for a local park or land conservancy.

The four ecological functions that all landscapes need to perform are supporting a diverse and complex food web, managing local watersheds, moving carbon from the atmosphere to the soil, and providing food and housing for as many species of native bees as possible.

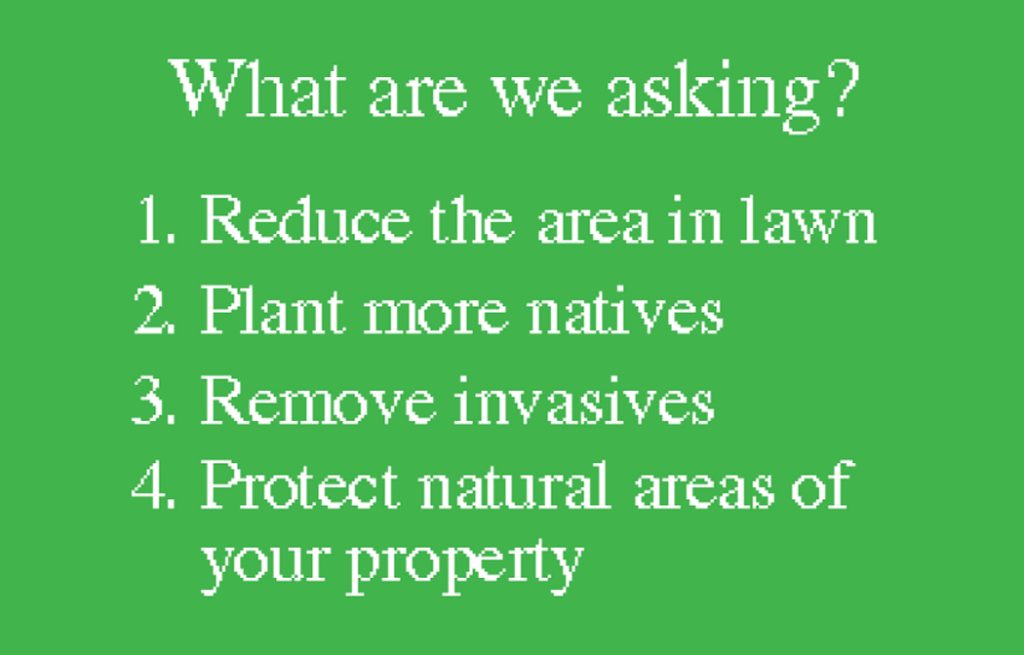

Lawn does none of these things well, so reducing the area we have in turf grass is a logical first step. But plants vary a great deal in how well they achieve ecological goals, so we must choose very carefully the plants we use to replace lawn. A handy tool to do just that can be found on the National Wildlife Federation website. Select “Native Plant Finder” and enter your zip code; a ranked list of ecologically productive woody and herbaceous plants for your county will pop up.

Diversity Loss? Not in Our Yard!

Recently, the World Wildlife Fund reported that Planet Earth has lost two-thirds of its wildlife since 1970. This jaw-dropping news joins a litany of recent reports about the decline of insects globally, the loss of three billion North American birds, and the prediction by the U.N. that one million species will go extinct in the next 20 years. Yet to those who justifiably conclude that the demise of our fellow earthlings is inevitable, I say, “Not in our yard!!”

For the past four years I have been photographing the moth species that live on our property. This year I reached 1,028 species on our ten-acre patch of southeastern Pennsylvania. And because each of those moths and the caterpillars they developed from are essential “bird food,” 59 species of birds have been able to breed on our property. And who knows how many additional bird species have used our land as a refueling site during fall and spring migration?

Not long ago, our property was part of a farm whose successive owners had worked the land hard for 300 years. But today, rather than having lost two-thirds of its wildlife, our ten acres have increased the number of its resident species by at least that much. The depleted agricultural wasteland of two decades ago has become a hotspot for local wildlife. How did this happen?

The seemingly astounding rebound in species on our property was neither astounding nor accidental. It was a predictable response by the natural world to our purposefully restoring nature’s foundation: native plants. The moths I am counting have returned because the native plants they require are here as well. And those plants are thriving on our property because, along with the wind and the local blue jays, we have planted them. We also have removed the tangle of invasive species so our native plants have enough space to grow. The birds and other vertebrates that live on our land can do so not just because of the moths our plants produce, but also because of the fruits and nuts our oaks, black walnuts, hickories, filberts, blackberries, serviceberries, dogwoods, persimmons, black cherries, pawpaws, chokeberries, viburnums, and black gums make each year.

Will our ten-acre restoration alone be able to reverse global declines in wildlife? Of course not, but if ecologically appropriate plant choices were consistently made by homeowners, land managers, and municipalities everywhere, the habitat value of all non-agricultural land would be measurably enhanced, just as it has been on our landscape in Pennsylvania. Aided by groups like the National Wildlife Federation, National Audubon, Wild Ones, Grow Native Massachusetts, the Missouri Prairie Foundation, and the California Native Plant Society, such transformations are well underway across the country, and the results are beginning to defy global wildlife trends.

You Are Nature’s Best Hope

Somewhere along the line we assigned earth stewardship to just a few specialists—ecologists and conservation biologists. The rest of us have had cultural permission to destroy the natural world whenever and wherever we wanted, using words like “development” and “progress” as rationalizations. This makes no sense; every human being on earth depends entirely on the quality of earth’s ecosystems, so why wouldn’t every one of us bear the responsibility of good earth stewardship?

The ecological approach to landscaping that I have described here is nothing more than basic earth stewardship, but it is stewardship that empowers us all to become forces in conservation. By choosing ecologically effective plants for your landscape, by shrinking your lawn, and by removing your invasive ornamentals, you will be able to make a difference that you can see—and enjoy—almost immediately. Life will return to your property! We all are nature’s best hope.

See a recommended list of Iowa native plants from the Southeast Iowa Sierra Club.

Excerpted with permission. All Rights Reserved © 2023 Homegrown National Park, Inc.