Last month, we took a hard look at economic growth to understand its connection to our most pressing environmental and social issues. While GDP growth can come with improved living standards, over-dependence on it can create vulnerabilities that affect every area of society. Even the inventor of GDP, Simon Kuznets, warned in 1934 that “the welfare of a nation can scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income.” If this is the case, why is GDP growth so often a major policy objective, and should it be?

Let’s look at where growth falls short and consider how “doughnut economics” could be a better model.

A Plan for Landing

Kate Raworth is one expert who has spent much of her career examining the growth paradigm. In her seminal book, Doughnut Economics, Raworth imagines how modern economists might draw a graph of growth. She believes that many would draw an exponential curve—in other words, one of infinitely increasing growth. But if economic activity is tied to the physical universe, exponential growth is more fiction than fact. Raworth explains that growth more likely resembles an S-curve, picking up speed in the beginning before an economy reaches maturity and levels off.

Perhaps one of the reasons we put so much hope into the idea of infinite growth is because we don’t know what a world without it looks like. Instead of trying to pretend-away reality, Raworth suggests that we imagine growth like flying a plane: rather than hoping that the plane will fly forever, we can prepare in advance for a graceful landing.

Relationships Are Key

Aside from the unrealistic expectation of infinite growth, there are more flaws to the GDP growth paradigm. One of the most fundamental issues is that by relying on a narrow measure of well-being, we implicitly emphasize the importance of transactional relationships over social contracts. It is well documented, for example, that monetary incentives can discourage prosocial behaviors because they stifle motivation. This is sometimes called the “incentive crowding” effect.

Take the following example: An elementary school is having a problem with parents picking up their children late, requiring the staff to spend additional time watching the children after school. To prevent this, the school begins charging late pick-up fees. It only takes a few days before there are significantly more late pick-ups than before! What is going on here? Well, prior to the fee, parents might have felt guilty about late pickups. After the fee is implemented, a new social contract is established, one in which a parent can simply pay for the convenience of coming late, guilt free.

In the above example, the financial incentive “crowds out” the moral incentive. With growth-addicted economies, we reinforce transactional relationships over other important ones. It is not hard to think of examples of this. How might commodifying natural resources change our relationship to nature? Or how might gentrification compromise the strength of local communities? What are the valuable relationships we jeopardize when economic growth takes priority?

The Sweet Spot

If growth cannot continue forever, and if relying on it can degrade important relationships, what should we aim for? The answer may lie in finding a balance, a “sweet spot,” where economic development meets the needs of society within the ecological boundaries of our planet. This is the essence of one of Raworth’s biggest contributions to economic thinking: the doughnut economy.

Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economy

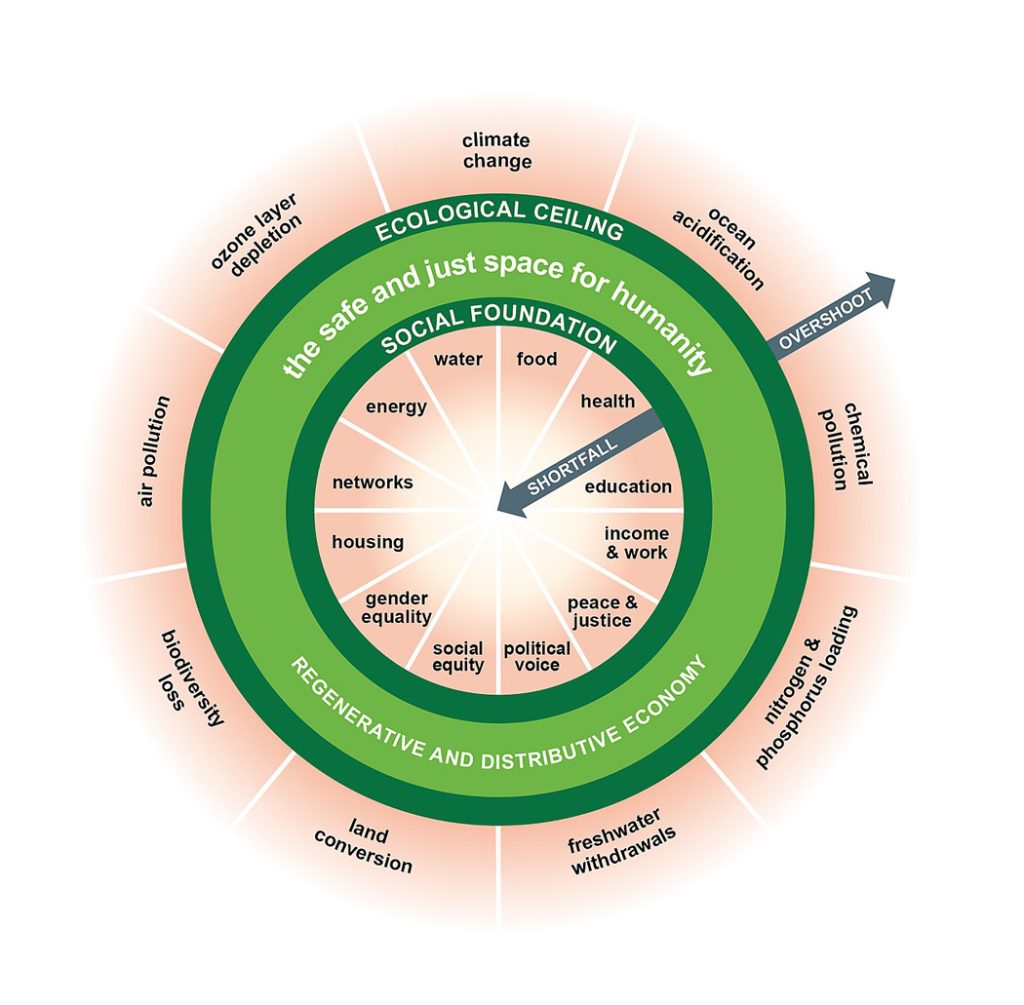

Rather than pursuing endless growth, the doughnut model encourages us to focus on achieving an economy that respects social foundations and operates safely within the capacity of the planet. In the diagram above, deviations from the doughnut inward represent shortfalls in social provisions, while deviations outward represent overshoots leading to ecological degradation. The body of the doughnut represents the place where both societal needs and environmental health are in balance.

The doughnut model encourages us to view progress holistically. By embracing the principles of doughnut economics, we can apply a more sustainable approach to development that prioritizes the long-term health of both people and the planet.