This article first appeared in the August 2002 issue of The Iowa Source. An exhibition of Pete Wettach’s photographs opens January 20 at the Herbert Hoover Museum in West Branch, Iowa.

In the winter of 1999, while I was working as an editor at the University of Iowa’s Institute for Rural and Environmental Health, a departing coworker handed me six small yellow-orange boxes, the contents of which would lead me to an astonishing treasure.

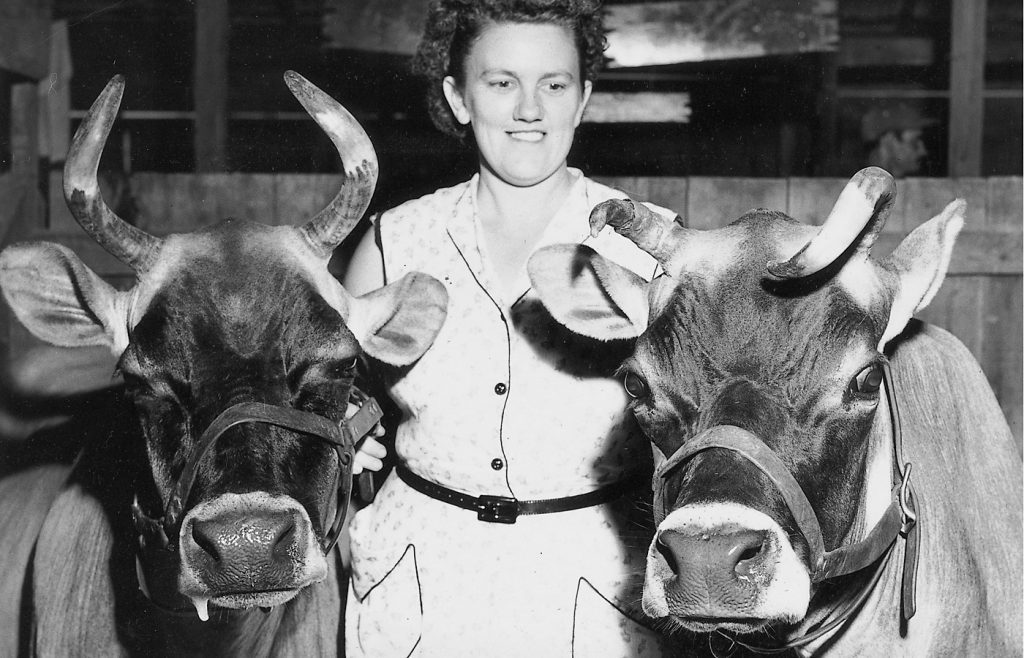

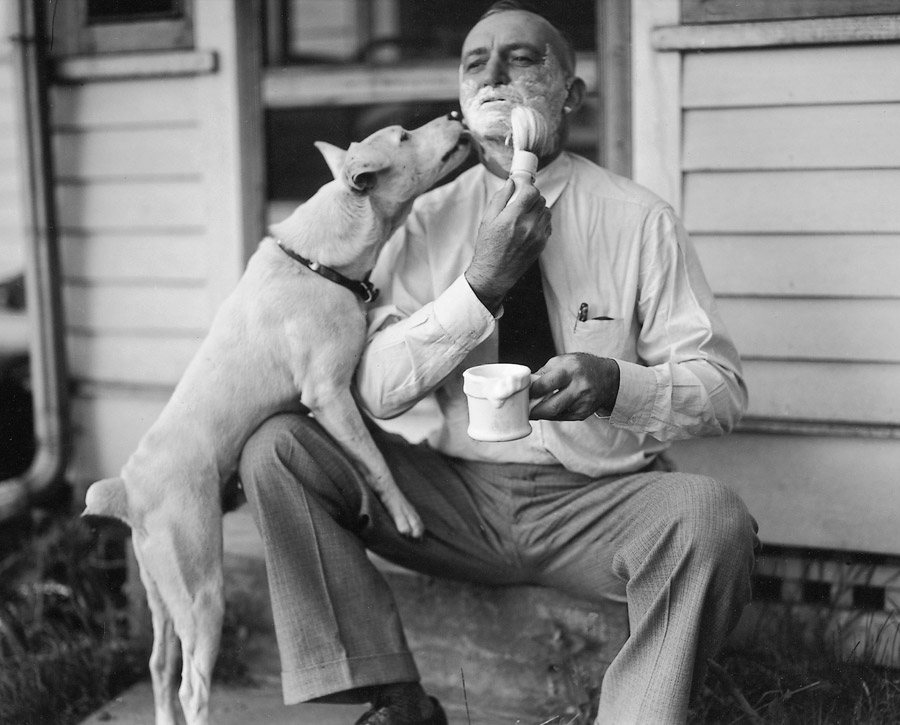

Each box contained between a few dozen and 200 black-and-white negatives. Two of the largest boxes contained negatives that were 5 x 7 inches in size. I had several developed to get a better look at them. The images were all taken on farms and looked to be from the 1930s or 1940s. Even an ordinary shot of a farmer on a tractor offered crisp textures in the crop growing up from the ground and the smooth metal of the machine under soft clouds. The photographer had an impressive talent for composition—nearly every photo begged to be framed. But what struck me most was the sense of warmth and camaraderie projected by the people in the photographs. It was as if they knew the photographer well and welcomed his presence. As a viewer more than half a century later, seeing what the photographer saw through the camera lens, I felt as if their open expressions were directed at me.

The boxes that held the negatives were the distinctive yellow-orange Kodak color, with the Kodak logo printed on the outside. On the side of each box was a heading printed in black felt-tipped marker, such as “THRESHING,” “HORSES,” or “CORN.” On the top of one of the boxes was pasted a preprinted label that read

A. M. Wettach

Agricultural Photographer

Mt. Pleasant, Iowa

This find created a little stir at the institute. Not only were these photos visually striking, they also offered a close look at a pivotal era in the history of the family farm. They showed how diversified Midwestern farms once were and how every member of the family participated in the work. There were photos of early tractors and the first combines, both of which revolutionized farming but also, along with other new technologies, changed the face of farming communities forever.

I am not a native Iowan or a Midwesterner. I am not a historian or a photographer. I have never lived on a farm. Nearly all the pictures in this book were taken before I was born. But these photographs struck a chord with me, bringing me back to look at them again and again.

Recording Everyday Farm Life

Wettach worked for the Farm Security Administration as a county supervisor in southeast Iowa during the 1930s and 1940s. A self-taught shutterbug, Wettach always brought along his camera as he traveled across the countryside visiting clients, documenting the profession of farming in the Midwest during a time of great change. As an agricultural photographer, he took pictures from the point of view of the farmer and sold them to farming magazines. His photographs show an intimacy and a familiarity with the subjects, who were frequently his friends, neighbors, family members, and clients. They celebrate farm life while also recording with staggering details its social and technological changes.

Ironically, the FSA is now better known for its photography project than for its farm rehabilitation program, including the one that Pete Wettach administered. The pictures taken by FSA photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Russell Lee, Ben Shahn, John Vachon, and others appear regularly in museums and books to this day. Although the FSA photographers took a wide variety of pictures of both urban and rural life during the Great Depression and World War II years, the project is most often remembered for its documentation of the bleak conditions of the rural poor.

But Pete Wettach never worked for this division of the FSA. During the early part of his career, he was a photographer on the side—a hobbyist—who also happened to work for the FSA in an office job. Instead of touring the country on assignment, charged with documenting the harmful effects of the Depression and the Dust Bowl years as the FSA photographers did, Wettach was completely on his own. Even later in his life, when he left government work to become a full-time freelance photographer, he still lived among and worked with many of the people he photographed. Most of the FSA photographers never had the opportunity to get to know their subjects well. Wettach, on the other hand, often had known the people he photographed for quite some time; in many cases he took pictures of them over the course of several decades. What he shared with the FSA photographers was their employer’s mission to improve the lot of the increasingly impoverished farm family. What Wettach saw through the lens of his camera, however, as a neighbor and friend of some of these struggling families, would prove to be very different from what the FSA photographers saw.

New Jersey to Iowa

Arthur Melville “Pete” Wettach was born on June 21, 1901, and grew up in Caldwell, New Jersey. One of four children, Melville, as his parents called him, was raised in a moderately affluent home. His father, Archibald Wettach, was a Swiss immigrant who served as a general clerk of courts, and his mother, Carrie Stewart Wettach, was a descendant of Christian Sharps, of Sharps rifle fame.

As he grew, young Melville developed a fascination with rural life, particularly with farming. He resolved to learn as much as he could about farm life, even working at a local dairy during high school, but he also began to think about leaving New Jersey for a part of the country where he could live on the land. A spread about Iowa in Country Gentleman magazine captured his imagination and, when he learned that Iowa State College had a good agriculture program, he made plans to go west.

Wettach arrived by train at Ames, Iowa, in 1919 at the age of 18 with 24 dollars in his pocket, and enrolled in Iowa State College. There he met William Allen Jennings, a fellow student who would become a close friend. It was at his first meeting with Jennings that Wettach decided to change his own first name to Pete, hoping it would help him fit into his new Iowa home better than the name Melville would. It was also during his college years that Pete met the young woman whom he would eventually marry: Ruth Grimes. Raised on a farm near Montrose, a small community of about 1,300 in Lee County, Ruth was studying home economics at Iowa State College. After Wettach graduated in 1923 with a degree in animal husbandry, Ruth’s family provided him with his first real taste of farm life as he spent the next year on the Grimes farm.

Farming & Photography

Ruth and Pete married in 1924, moving back to Ames when it became clear that the Grimes’s farm earnings were insufficient for two families. While he was helping on the Grimes farm, Wettach found time for another pursuit: photography, probably using a basic camera that he and Ruth brought along on car camping trips with W.A. Jennings. Even if the camera was not particularly fancy, Wettach made good use of it and his knack for photography began to attract attention.

In 1928, the Wettachs’ first and only child, Robert Stewart Wettach, was born. Later that year the family moved to New Hampton, Iowa, where Pete took a job teaching vocational agriculture in high school. After just one academic year, the Wettachs decided to leave New Hampton to finally fulfill Pete’s longtime wish to be a farmer.

But his dream of farming was doomed almost from the very beginning. The 1920s had not been particularly prosperous times for farmers, but prices bottomed out so precipitously in the early 1930s that many farm families faced grinding poverty.

Despite the constant difficulties, sometime during these years Pete scraped together the money to buy the secondhand camera that he would use for much of his early career, taking some of his most striking pictures with it. This camera, most likely a Graflex 5 x 7 Series B, exposed large negatives of 5 x 7 inches, allowing for great detail and beautiful quality. It was a camera for serious photographers and photojournalists, one that would help Wettach take much better photographs than he had been able to before. It was extraordinarily cumbersome to use by today’s standards, however. The camera was heavy and large, weighing 11 or 12 pounds. The large viewfinder unfolded on the top, while a lens protruded from a trap door in the front. A photographer would have to look down into the viewfinder to see the subject, which was reflected by means of a large mirror facing the lens.

Only one photograph could be taken at a time. The camera had no light meter (they had yet to be invented) and no flash attachment. A brass plate on the side provided a lookup table to calculate exposure time. Film speed, not yet standardized, varied depending on the film manufacturer.

To take a picture with a 5 x 7 Graflex Series B, Wettach would have had to balance this heavy box with his left hand at waist height, adjusting the aperture and tension with his other hand, all while looking down into a viewfinder that offered a reversed image of the subject. Figuring out the proper shutter speed was an exercise in educated guesswork. After each shot, he would have to spend at least 15 to 30 seconds to reset the camera after every shot. And, unless he had a black bag or box for loading film, he would not have been able to take more than one or two dozen pictures without returning to his darkroom—often a long drive over rural roads—to reload film.

Despite the painstaking work involved, Wettach took thousands of photographs with his 5 x 7 Graflex. Of the tens of thousands of Wettach negatives now housed at the State Historical Society of Iowa, about 4,200 are in this format. Most of the remainder are 4 x 5 inches in size, taken by a smaller Graflex or similar format camera. Wettach owned several other cameras during the course of his career, including a Hasselblad and a 35mm Leica.

Despite the relatively primitive conditions on the farm, once Wettach purchased his Graflex camera, he began to experiment with photography, reading manuals and magazines and teaching himself to take pictures, develop the film, and make his own prints. As Wettach’s skills with photography improved, he began to submit his photos to magazines that already regularly bought his articles. He continued to make most of his freelance income from writing, but every now and then over the next few years the Wettachs’ farm account books would show some income from photos.

A New Career

Despite their best efforts, the Wettachs simply couldn’t make it in farming. In mid 1935 they sublet their land and Pete took a job as a county supervisor with the federal government’s Resettlement Administration, an agriculture relief program that would, ironically, put him to work helping keep other farmers from going under as he had. They moved some 55 miles north, to Mount Pleasant, Iowa, the seat of Henry County and the location of the Resettlement Administration’s regional office.

In 1937 the Resettlement Administration became the Farm Security Administration, an agency of the Department of Agriculture. The FSA oversaw several farm relief programs, including one called the Tenant Purchase (TP) program, in which renting farmers could apply for government loans to purchase their own farms. Not surprisingly, the TP program was popular and competition was fierce among renting farmers hoping to become owner-operators. Applicants to the TP program were carefully screened, and once approved, closely monitored.

As an FSA county supervisor, Pete Wettach worked closely with the farm families in this program. His work took him out to many individual farms across a broad swath of rural Iowa. At one point his territory included nine counties (Lee, Van Buren, Henry, Des Moines, Louisa, Muscatine, Scott, Cedar, and Clinton), comprising a large portion of the southeastern quadrant of the state.

By the early 1940s, Pete Wettach had developed a regular relationship as a freelance photographer and writer with several farming magazines, including Wallaces’ Farmer, a nationally popular biweekly newspaper launched by the Wallace family in the late 19th century. The Wallaces’ Farmer masthead credo, “Good Farming, Clear Thinking, Right Living,” underscored the publication’s goal to help link isolated farm families while educating them about scientific farm practices, health and safety issues, political initiatives, and national and world affairs.

The biggest unanswered question about Wettach’s 14-year career with the FSA is: What did he know, or think, of the FSA’s now-famous photography project? From 1935 to 1943, while Wettach was quietly taking thousands of photographs of farms and farm people, his employer was sending out photographers to take pictures of rural scenes all over the country, including Iowa and its neighboring states. The FSA photographers, however, were specifically commissioned to document the toll of the economic and natural disasters of the 1930s in order to bolster public support for Roosevelt’s New Deal relief programs, especially during the mid and late 1930s. Several of these photographers built their artistic reputations while promoting the FSA’s agenda. Wettach had no such agenda to guide the target of his camera lens, but he did have a sensitivity to the experiences of his friends and neighbors. He considered their lives to be worth recording on film.

Warming to his Subject: Rural Farmers

Since he was a self-employed independent photographer, Wettach’s approach to taking pictures during the Depression and later years was molded by a combination of his own vision and those of the magazines and newspapers that bought his photographs. His pictures tend to emphasize resilience instead of devastation, incremental successes instead of failure, humor and warmth instead of loneliness. If the FSA’s photography project helped us understand what it was like for American farmers to hit bottom, then Wettach’s photographs can teach us how they climbed out of the abyss.

The subject matter of his photographs varies greatly, but it almost always concerns farm life. Despite (or maybe because of) his painful failure as a farmer, Wettach retained a romantic enthusiasm for the intrepid farm families who stuck it out. He was not bitter, although he was undoubtedly wiser, funneling his admiration for farming into his craft as a photographer and using that craft as a tool to describe the simple joys and harsh realities of life on the land.

At first Wettach took pictures of people he knew: his family members such as the Grimes family and Ruth and Bob, local farmers, and his or his colleagues’ FSA clients. His subjects were mostly from Henry County but also included many from his FSA counties and adjacent areas. Over time, especially when he was able to travel as a freelancer, the geographic range of his photos reached other corners of Iowa and later other states around the nation.

“The idea was to take photographs of subjects that I liked and then try to find a buyer,” Wettach wrote later in life, and it was this mindset that produced a huge volume of photographs of men, women, children, animals, crops, and machinery, designed to document and often to celebrate farm life. Despite the realities of his photography business, however, Wettach never completely left behind his artist’s sensibilities when taking pictures. His striking photographs impressed people, even if they did not necessarily think of his work as art per se. Robert Wettach remembers his father expressing annoyance when someone said to him, “Gee, you must have a really nice camera!”

“That’s a little like telling a painter, ‘Gee, you must have a really nice paintbrush!’ ” Pete Wettach would complain.

Wettach set up his business to provide stock photographs, which meant that he had to develop a ready supply of images on a variety of subjects to offer to publications as they needed them. He organized his enormous collection of negatives by subject rather than by date or location, marking hundreds of film boxes with labels such as “SHEEP,” “THRESHING,” or “HANDY IDEAS.” A single box could contain more than a hundred negatives taken over a period of 20 or 30 years.

Browsing through copies of Wallaces’ Farmer from the late 1930s, the 1940s, and into the 1950s is a bit like looking through a catalog of Pete Wettach’s work. The use of his pictures in this publication was routine, with photos sometimes appearing in nearly every issue for several consecutive months. Some photos were decorative and unrelated to the text, such as a photo in a winter issue of a horse pulling a sleigh, while others illustrated themes presented in articles.

In 1949, Wettach decided to leave government work for good and strike out as a full-time freelance photographer. The FSA had by then become the Farmers Home Administration, and its mission had evolved through the Depression and World War II as the economic conditions improved for farmers during the war and postwar years. He began to travel more widely, often with Ruth, and he also began to take some of his pictures in color.

With more time to spend exclusively on photography, Wettach took many more pictures than he had before. His subject matter became more technical than it had been, in response to farm publications’ interest in keeping up with the latest scientific and technological developments in agriculture, but he never lost his artist’s eye.

Reprinted with permission from A Bountiful Harvest: The Midwestern Farm Photographs of Pete Wettach, 1925-1965, by Leslie Loveless, published by the University of Iowa Press.

To Order Books

A Bountiful Harvest is available from the University of Iowa Press or on Amazon.com.

To Order Digital Prints

Contact the State Historical Society of Iowa at iowaculture.gov.

Quotes:

Pete Wettach’s first professional camera, a Graflex 5 x 7, was extraordinarily cumbersome. Heavy and large, it weighed 11 or 12 pounds.