When you’re a 16-hand, 1,100-pound American Thoroughbred horse, just standing all day can be stressful on your back, neck, and shoulders. When Hampton isn’t grazing in his pasture or hanging out with his buddies, he participates in vigorous hunter-class competitions, making him one of the many types of performance and work horses who need a back rub every now and then to stay on top of their game. Many horse owners have turned to equine massage.

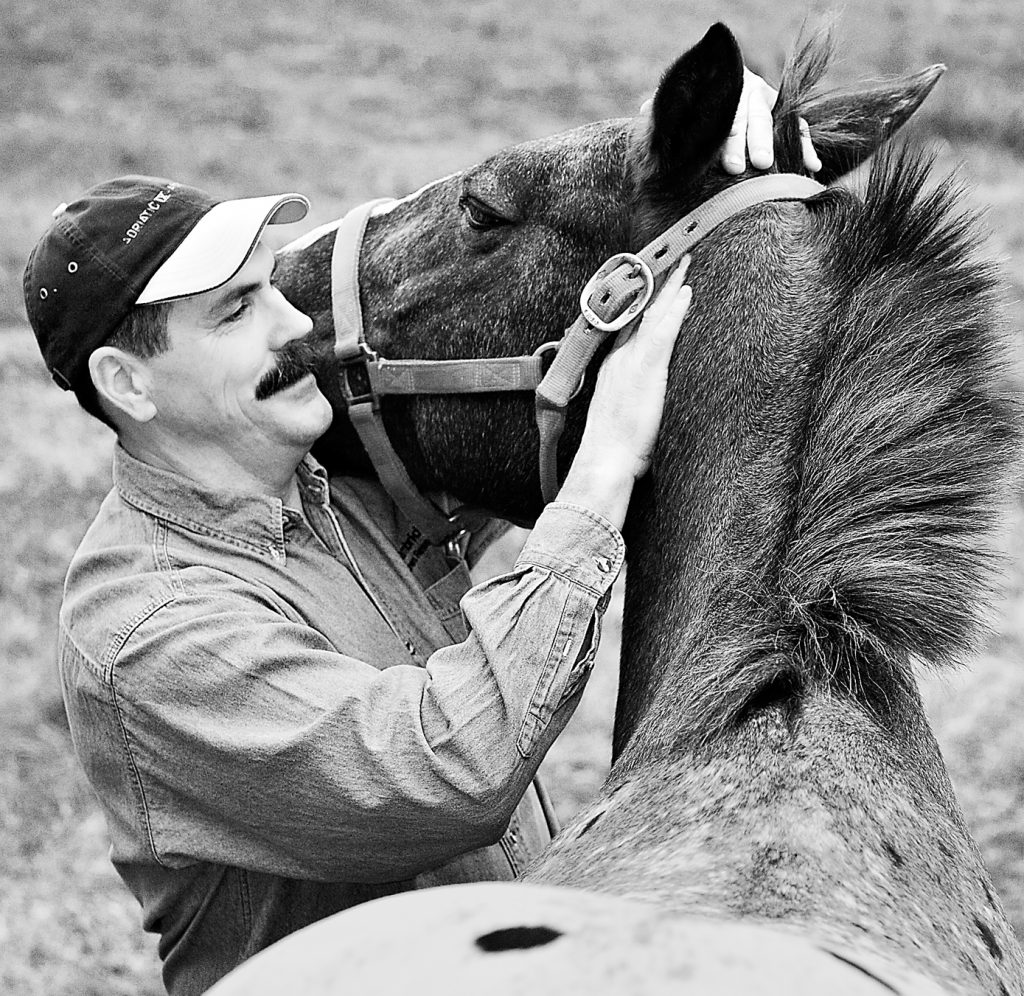

Enter Jim Masterson.

He’s spent the last ten years perfecting an integrative technique of equine massage that incorporates the best of acupressure, neuromuscular release, and cranial-sacral therapy—a therapy that can help performance horses like Hampton relax and get their spines and nervous systems back in order before they have to perform again.

“It doesn’t matter whether it’s dressage, hunting/jumping, barrel racing, standardbred harness racing, or Amish draft horsing,” Masterson says. “Work and performance horses are exposed to a lot of physical stress. Left undetected and not dealt with, accumulated stress can cause performance and behavioral problems.”

Jim’s approach employs a protocol he terms “search, response, stay, and release:” finding the compromised area, watching for a response, applying pressure, then backing off and gauging the success of the adjustment by the horse’s reaction. This could be eye blinking, yawning, licking his lips, shifting, snorting, showing his teeth, stretching his neck, or shaking his head.

“Practitioners of my technique will develop a real sense of touch and feel for the horse and his responses,” Jim says. “Let’s say I am massaging the forehead and his eyes soften, but he pulls away. That’s a sign he is not relaxed yet. I’ll have to go slowly and carefully watch his responses.”

Asset to the U.S. Equestrian Team

A crowning moment for Jim’s eight years of researching and developing the Masterson Method came in August when he was invited to accompany the U.S. Equestrian Team at the World Equestrian Games in Aachen, Germany. Two-time WEG endurance-race winner Valerie Kanavy had been impressed with Jim’s work at a certification course in Ocala, Florida. Kanavy was to be the Chef d’Equipe (team captain) of a team of six horses and riders who would race a grueling 100 miles as the ultimate test of endurance. Kanavy enlisted Jim to “Masterson Method” the horses before the event.

After the race, rider Kathyrn Downs of Somerville, Maine, called Jim a “great asset to the U.S. Endurance Team,” noting that he won over her standoffish horse Harley “with his quiet ways and gentle manipulations. Jim enabled Harley to have a sound and successful race. . . .”

Patience, Feel, and Response

Prior to any performance event, Jim chooses a work space large enough for the horse to turn full about during the session but small enough for him to be able to develop a rapport with his ward.

“It’s about taking the time,” Masterson says. “This is nothing that can be done in a hurry. If the horse senses you are not relaxed and don’t have time for him, then he probably won’t let you work on him to any real advantage. If he senses that you are there to help him, and are willing to move slowly, then he will likely do anything you ask.”

With Hampton, Jim moves his hands over the horse’s structural meridians, checking for any tender areas that might require his immediate attention, then moves onto the poll, the area at the top of the head behind the ears.

“The horse is an amazingly receptive animal,” Masterson says. “Just the heat from your hand encourages circulation and helps the muscles start to relax. Using several levels of pressure, from no more than that required to rub the hair on your arm, to pressing on a grape, an egg yolk, a ripened lemon, or a hard lime, it’s about touch and feel, and the response of the horse,” he says.

Jim gently touches an area on Hampton’s shoulder and the horse starts to blink, shift his legs, and fidget overall. “Horses get a little uncomfortable when it’s hard to let that sore muscle go,” Jim says, unrelenting in massaging the tender spot.

Hampton soon responds that the muscle has released the tension, letting his breath go in heavy sigh. As Jim continues to move his hands along Hampton’s spine all the way to his hoof meridian, the horse lightly snorts. Other signs that the adjustment has been successful come from, well, the horse’s mouth: Hampton is licking his lips, shaking his head, neighing, snorting; then, friskily, he turns half about to let me enjoy his breath on my neck. (I think I’m in love.) After about a minute of this multi-faceted releasing he still wants to yawn, but it won’t come out.

“He’s got something in there that’s still bothering him,” Jim advises. “He wants to yawn big.”

Time for the TMJ (temporal mandibular jaw joint) adjustment. Removing Hampton’s halter, Jim puts his hands in the horse’s mouth and ever so gently pushes his upper and lower jaws in opposite directions.

“This is a tricky one,” Jim warns would-be practitioners. “You want to move the jaws just a fraction past where they want to go; otherwise, you can make the horse’s jaws sore.”

As predicted, within seconds of the adjustment, Hampton yawns fully, delivering release response number eight.

Several other points are cleared, and now Hampton is led back to the pasture for more play in the warm Indian-summer sun of Iowa.

Deepening Communication

“When accumulated stress in your horse’s connective tissues and muscles is released, owners will notice increased mobility and range of motion in their horse, improved jumping, bending, and stopping, and increasing trust,” Masterson says.

Hampton affirms that. He gallops forth happily, if his whinny is any sign, telling the others where he’s been and how good he feels. The whole process took about an hour. When he works at a major event, Jim will see eight to ten clients in a day.

“It is my hope that the Masterson Method will lead to not only deep muscle and tissue release for the horse,” he says, “but a new and exciting way of communicating between horse and owner. We don’t have to shout for the horse to hear us . . . we can whisper and the horse will listen, and if we are listening, the horse will answer.

And just maybe you’ll hear him say, “Hey, Wilbur, get Jim on the phone, will ya?”

Do Try This At Home!

You can learn these techniques to use on your own horse with Jim’s 75-minute Equine Massage for Performance Horses DVD, reviewed in the October issue of Western Horseman magazine. Jim, who is certified in equine sports massage and soon to be certified in equine cranial-sacral therapy, also teaches seminars in the Masterson Method. See www.mastersonmethod.com to learn more.

Do Horses Get Headaches?

“Absolutely,” says Masterson. Jim notes that when a horse is head shy, pulls back, or otherwise shows fear when you enter the stall that it could possibly be a headache emanating from a jammed up spot in the vertebra behind the poll or occipitals (head and neck area).

Using only the pressure it would take to press on a soft lemon in his hands, Jim massages a spot behind William’s left ear. William soon drops his massive head onto Jim’s shoulder. His nostrils widen, he sighs deeply and totally relaxes while Jim continues to assess through William’s responses how much more pressure to apply for deeper muscular/skeletal release.

William is almost asleep now, his head turned to the side, he continues to release as evidenced by deep breathing, panting, licking his lips, dreamily baring his teeth and attempting to yawn. Jim releases the pressure and steps back to allow William to adjust to the new feeling. William thanks Jim with a loud snort, shakes his head down low and up high and rotates full about his 17-hand form in the stall, turning back to attack a patch of salt lick on the wall which did not interest him at all earlier.

It’s been a successful session.

Is Jim a Horse Whisperer?

Not officially. Horse whisperers are usually trainers who have a special talent for helping lame horses mend, but he does “whisper” when he’s communicating with the horses.

To contact Jim Masterson, visit his website, mastersonmethod.com, or call (641) 472-0976.